Changing the Tune

The evolution of the theme tunes of popular British children’s television programmes offers a useful prism for looking through at processes of ideological change and globalisation.

Please support my work by becoming a free or a paid subscriber to the newsletter. Paid subscribers are vital to me being able to continue producing and expanding this newsletter.

You can also support my work by making a one-off payment, at a price you consider affordable.

This post is part of the newsletter’s regular ‘Research and Reflections’ series, consisting of pieces based on my ongoing academic research, as well as on my musings on and responses to current affairs and personal developments.

I recently wrote a piece on Postman Pat: Special Delivery Service, the updated version of Postman Pat – whose first series ran way back in 1981 – screened on CBeebies between 2008 and 2017. I got a lot of excited responses to it, which I’ll attribute to being part of a generation that grew up on that first series of Postman Pat, and then watched the SDS series with their kids (and liked it a whole lot less).

One of the things that struck me is how many of those responses centred on the matter of the programme’s theme tune, or rather, its closing theme. The opening theme tune is an only slightly (but significantly!) altered version of the original. Yet it is the entirely different closing song that now functions as an unwelcome earworm for beleaguered millennial parents.

This got me thinking about how alterations to the theme tunes and credit sequences in new versions of older children’s programmes demonstrate broader thematic changes between those original and later series, and their underlying accompanying ideological shifts. There are plenty of examples of this trend, but I wanted to focus on three in particular: Postman Pat; Fireman Sam; and Thomas & Friends. This is because these were three programmes that all were first made and aired in the 1980s, set in rural communities, depicted public services – the postal service, the fire brigade, and (talking) railway engines – and yes, very popular with one particular small boy born in North London midway through that decade.1

Postman Pat

The opening credits to the original series of Postman Pat simply featured Pat and Jess driving around Greendale in Pat’s van (with Pat getting out at one point to deliver letters). The theme was written by composer Bryan Daly and sung by Ken Barrie – who also narrated the programme and voiced all of its characters – accompanied primarily only by acoustic guitar. This simple folksiness matched Postman Pat’s rural setting.

Lyrically, the theme tune captured the familiarity of workday routine and rural community life, and Pat’s contentedness with his lot, both emphasised in the episodes themselves. It also invited the child viewer into this world as a potential recipient of the post, a ritual given an added degree of enchantment and drama by its being referenced in the bridge:

Postman Pat, Postman Pat

Postman Pat, and his black-and-white cat

Early in the morning

Just as day is dawning

He picks up all the postbags in his vanPostman Pat, Postman Pat

Postman Pat, and his black-and-white cat

All the birds are singing

And the day is just beginning

Pat feels he’s a really happy manEverybody knows his bright red van

All his friends will smile as he waves to greet them

Maybe, you can never be sure…

There’ll be knock (knocking sound)

Ring (doorbell sound)

Letters through your door (heh-heh)Postman Pat, Postman Pat

Postman Pat, and his black-and-white cat

All the birds are singing

And the day is just beginning

Pat feels he’s a really happy man

Pat feels he’s a really happy man

Pat feels he’s a really happy man

By the mid-2000s, that opening credit sequence had changed, beginning with an opening shot of Greendale from above and showing Pat actually interacting with other characters on his rounds. However, visually it followed essentially the same narrational logic of the original credits, while the theme music itself was unchanged.

Series 3 to 5, however, did feature a different closing theme and credits sequence. The original had simply shown Pat looking at a series of letters while Barrie performed a mostly wordless version of the theme tune. The new closing song, written by Simon Woodgate, sounded more contemporary in its production, its fuller sound rounded out with female backing vocals:

However, with an envelope in the background featuring the programme’s credits and lyrics concerned principally with what might be in Pat’s bag (a letter, a parcel, a postcard, or, of course, Jess the cat), it connoted little by the way of change in the idea as to what the postal service (or a job delivering the mail) was.

Postman Pat: Special Delivery Service’s opening credits drew upon the earlier motif of Pat doing his rounds, making deliveries to familiar faces. However, the sequence – set off with an early close-up of Pat’s gleaming SDS badge – now displayed the expanded geography of his world, incorporating not only the village of Greendale, but the nearby larger town of Pencaster too. It also showed off the broader array of transport he had for getting around it, including his motorcycle and helicopter, at one point parachuting parcels to the children below. Musically, it began with a new version of that famous theme tune, with synthesised strings instead of sparse acoustic guitar. There was one small but integral lyrical change on the song’s bridge, however, with it now being ‘parcels to’ rather than ‘letters through’ your door; a line visually accompanied by Pat completing a somersault to rescue a startled Jess.

This encapsulated the transformed idea of postal work as a public service at the heart of Postman Pat: Special Delivery Service compared to its predecessor. To quote my earlier piece:

Special Delivery Service, by contrast, reflected two major shifts that had occurred since the outset of the twenty-first century. Under New Labour (and subsequently the Coalition government), Britain’s postal services underwent a process of incremental privatisation and marketisation, including the differentiation of the ‘Royal Mail’ brand from the ‘Post Office’ one, and then the end of its monopoly on postal deliveries. SDS likewise functions as a distinguishing occupational identity for Pat, connecting him to the Pencaster mail centre, and involving far less interaction with Mrs Goggins and Greendale’s own Post Office. Secondly, with the rising advent of the internet, the volume of letters being handled by the postal services declined, in contrast to the increasing delivery of goods being ordered online, as highlighted in a 2008 government-commissioned review of the sector. Pat’s shift to standalone deliveries of big-ticket items with particular rationales behind them likewise reflected this change.

The closing credits sequence visually echoed earlier ones, a single shot focusing on Pat and Jess in front of Pat’s new larger van (and one of farmer Alf Thompson’s cows). Yet its new accompanying theme, again written by Simon Woodgate, reinforced the branded differentiation of these series from their predecessors, and the SDS from the older Royal Mail, whose logo does not adorn the sides of Pat’s newer vehicles.

Again, there is a far fuller, more contemporary sound to this tune, with synthesised strings and childlike shouted backing vocals. Lyrically, the self-consciously transformed idea of postal work evident in the programme is fully evoked:

Special Delivery Service

Pat’s on his way

Special Delivery Service (S-D-S!)

What’s it going to be today?(Postman Pat, S-D-S

We all know that he’s the best!

Mission accomplished!)

Not only does this reinforce the idea of the SDS brand; it also reiterates that Pat is not simply an ordinary postman, but a superlative example of one, and that his work is not routine but bespoke, focused on a single high-profile delivery and its completion.

Fireman Sam

Fireman Sam (or Sam Tân, to give it its original Welsh-language title) was originally commissioned by Wales’s S4C, and produced by Weston-Super-Mare-based Bumper Films. The first series was broadcast in 1987, episodes appearing in Welsh on S4C and in English on BBC 1 shortly afterwards. Three further series appeared in 1988, 1990, and – after a brief hiatus – 1994.

The programme, shot using stop-motion animation, focused on Sam, a firefighter in the fictional Welsh village of Pontypandy, and his fellow firefighters Elvis Criddlington, Station Officer Steele, auxiliary Trevor Evans, and later, Penny Morris. They served a community including shopkeeper Dilys Price and her mischievous son Norman, Italian café owner Bella Lasagne, and Sam’s twin nephew and niece, Sarah and James.2

The opening credits sequence shows Sam waking up in the morning, showcasing a couple of the budding amateur inventor’s household gadgets, before he is picked up and taken to work in a fire engine by Elvis, with brief interactions with other community members along the way.

The famous theme tune is jaunty and up-beat, synthesisers accompanied by electric guitar, with Welsh singer Mal Pope joined by backing vocalists on the chorus. Whereas musically, the original Postman Pat theme sounded like it might have been recorded a decade earlier than it was, Fireman Sam’s was very much of its time, and also captured the spirit and rhythm of Sam’s more dramatic working life. Lyrically, however, there were many parallels. The original Welsh-language version translates as follows:

Another day has come

Sam as prompt as ever

Getting ready to go to work

Start out on his journeyDrive the red engine

Sam, Fireman Sam

Ring, ring the bell

Sam, Fireman Sam

Sam from Pontypandy

The hero of our little villageAll waiting on the street

Sam comes every day at the same time

This is Sam, oh, there he is

“Good morning”, “Goodbye”, “Good morning”Drive the red engine

Sam, Fireman Sam

Ring, ring the bell

Sam, Fireman Sam

Sam from Pontypandy

The hero of our little village

The English-language version (which Pope also sang), was as follows:

When he hears that fire-bell chime

Fireman Sam is there on time

Putting on his coat and hat

In less than seven seconds flatHe’s always on the scene

Fireman Sam

And his engine’s bright and clean

Fireman Sam

You cannot ignore

Sam is the hero next doorDriving down the busy streets

Greeting people that he meets

Someone could be in a jam

So, hurry, hurry, Fireman SamHe’s always on the scene

Fireman Sam

And his engine’s bright and clean

Fireman Sam

You cannot ignore

Sam is the hero next door

The English language version is less place-specific, with a greater emphasis on the speed and excitement of his work. Yet they both root Sam’s heroism in his proximity to the viewer and, along with the scenes portrayed in the opening sequence, emphasised his familiarity with the community he serves.

In 2005, Fireman Sam returned on S4C and BBC. S4C had sold half of its stake to Gullane Entertainment – formerly the Britt Allcroft company, which originally brought Thomas & Friends to the screen (more anon) – which was itself subsequently bought by American conglomerate HiT! Entertainment. This fifth series introduced an updated version of the original stop-motion style, and was animated by Siriol, a longstanding producer of animated programming for S4C that was now a subsidiary of the British media conglomerate Entertainment Rights. It featured a handful of new characters, including Australian rescue pilot Tom Thomas, and interracial couple Mike and Helen Flood and their daughter Mandy, a continuation of the show’s tendency towards portraying diversity in rural Wales.

The series also introduced a new set of opening credits, over a montage sequence mainly comprising action shots of Sam and his colleagues (and the local brigade’s vehicles) performing an assortment of rescues.

These were accompanied with an updated version of the theme tune, featuring a rockier instrumental and vocals, and different lyrics. In English, these were as follows:

When he hears that fire alarm,

Sam is always cool and calm

If you’re stuck, give him a shout

He’ll be there to help you outSo move aside and make way

For Fireman Sam

‘Cause he’s gonna save the day

Fireman Sam

‘Cause he’s brave to the core

Sam is the hero next doorIf there’s trouble, he’ll be there

Underground or in the air

Fireman Sam and all the crew

They’ll be there to rescue youSo move aside and make way

For Fireman Sam

‘Cause he’s gonna save the day

Fireman Sam

‘Cause he’s brave to the core

Sam is the hero next door

The Welsh-language version translated roughly as follows:

Another call, away with Sam

In his red engine like a flame

Driving through the area to save everyone

From the house, or down from the roofLook, here he comes

Sam, Fireman Sam

Because the goal is to help everyone,

Sam, Fireman Sam

There is no one like you,

The hero of our little villageIt doesn’t matter where you are

In a black pit, or up high

Sam and his crew will come racing

They are sure to get you outLook, here he comes

Sam, Fireman Sam

Because the goal is to help everyone,

Sam, Fireman Sam

There is no one like you,

The hero of our little village

These different lyrics (and the new opening credits) implied a shift to a different type of heroism: more all-action, more out of the ordinary, less emphasis on his reciprocal relationship with the village community (whereas Bella provided him with his wrapped lunch in the original version, now she blew kisses after him).

S4C subsequently sold its remaining 50% share to HiT!, and would thereafter be produced in CGI rather than stop-motion, with ten more series having been made since 2008. In the UK, these episodes have been shown firstly on pay TV channel Cartoonito, and terrestrially on ITV’s Fluffy Club programme, and then, since 2012, on Channel 5’s Milkshake set of programming for children.

As the programme entered the fully digital realm, so its characters became increasingly exaggerated into their characteristics: Elvis from mildly clumsy to nearly completely incompetent; Norman from a bit of a tearaway to budding pyromaniac.3 As for Sam, he became really, really buff. Pontypandy was turned into a coastal town (allowing for maritime as well as land-based adventures), and new characters were subsequently introduced in keeping with these geographical changes, such as Sam’s fisherman brother, Charlie.4 Aided by CGI, the fires and other disasters got bigger, and characters began responding to them by saying things like ‘I’ll call Fireman Sam’ specifically, rather in keeping with his transition from an everyday firefighter to some sort of quasi-superhero.

The opening credits sequence got shorter, comprising a digitised equivalent to the kinds of scenes shot using stop-motion for Series 5. Through until Series 13, it also used a truncated version of the same theme, comprising only the first verse and chorus. Sam kicking a door of a burning building open on the ‘Cause he’s brave to the core’ line neatly captured his character’s transformation.

Reflecting the widening remit of emergencies he and his (expanded) coterie of colleagues deal with, since Series 14 (in 2022) onwards Fireman Sam’s opening credits and accompanying theme have instead foregrounded ‘The Rescue Team’.

When they hear that fire alarm,

The Rescue Team stays cool and calm.

If you’re stuck, give them a shout

They’ll be there to help you outFireman Sam is on the way

With the Rescue Team

Sam is gonna save the day

With the Rescue Team

‘Cause they’re brave to the core

They are the heroes next door

This balancing of Sam’s protagonist status with a broader cast of characters performing a wider range of rescue is an interesting shift in the programme’s dynamic, between the logic of the hyper-heroic individual and of the all-encompassing corporate entity. If they now seem like a Welsh human equivalent of the Paw Patrol, that perhaps is an unsurprising by-product of the show’s marketing to a more global audience, making the institutional specificities of representing an individual rescue service as it operates in Wales or the UK more generally less relevant.

Thomas & Friends

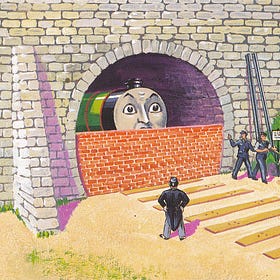

Of the three franchises, Thomas & Friends is the one that dates back the furthest, having its origins in the Railway Series of books, the first 26 volumes of which were written by the Rev. W. Awdry from 1945 to 1972 (his son Christopher Awdry would later take up the mantle, writing a further 17 between 1983 and 2011). These stories, set in what would become the fictional Island of Sodor, depicted a world of (almost all-male) talking engines, and combined the Reverend’s railway enthusiasm with a Christian ethics centred on the importance of hard work, humility, and obedience, and a narrative structure focused around pride, fall, penitence, and redemption. Those often translated into quite conservative politics around questions of gender, labour, and modernisation.5

Thomas himself was something of a first among equals in this fictional universe, being numbered quite literally ‘1’ on the side of his cab. He did not appear in the first book, The Three Railway Engines (1945), but was the central protagonist of the second and forth, Thomas the Tank Engine (1946) and Tank Engine Thomas Again (1949). He was a significant, if only sometimes central, character in subsequent books as the range of engines and indeed railways operating on Sodor was broadened. Yet his relatively early appearance in the book series and his childlike cheekiness made him an obvious point of identification for young readers of and listeners to the stories.

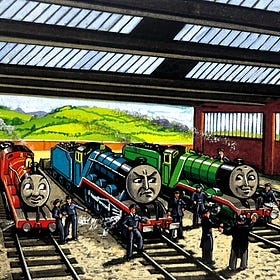

There were several failed attempts to adapt the Railway Series for television from the 1950s onwards, before producer Britt Allcroft successfully purchased the television rights in the early 1980s. She worked with British animated productions firm Clearwater Features and Central Independent Television to make the first two series of Thomas the Tank Engine & Friends, mainly using real model trains, narrated by ex-Beatle Ringo Starr, and screened on ITV between 1984 and 1986. The first series was based almost entirely on first eight Railway Series books; the second mostly on subsequent volumes written by Wilbert Awdry that focused on the original railway (along with a handful of newer ones written by Christopher Awdry). This served to restrict the cast of engines involved, only slightly expanded in the second series; Thomas was often the main character in these episodes, but also did not feature much in others.

The wordless theme song, written by Mike O’Donnell and Junior Campbell, was performed on synthesisers but imitated a combination of piano keys with sounds like puffs and whistles. On the opening credits, it accompanied a sequence of shots of Thomas making his way across Sodor’s railway, emphasising his centrality to the show’s concept, even if the ‘Friends’ were more prominent in the ensuing episode.

There were also a broad range of other pieces of incidental music that accompanied other engines and were intended to encapsulate aspects of their character, such as Daisy, the ‘highly sprung’ diesel railcar whose disdainful laziness was communicated in part via a synth-heavy theme that is basically sexism in musical form.

A third series of Thomas & Friends, produced entirely by Britt Allcroft Company, appeared on VHS in 1991 and then was broadcast on ITV in 1992; the fourth similarly was released firstly to video in 1994 and 1995, before making its television debut instead on satellite channel Cartoon Network. The episodes, now narrated by Michael Angelis, were still more often than not based on stories from Wilbert Awdry’s Railway Series books, introducing a broader range of characters from them but also featured stories written by Andrew Brenner for the Tank Engine & Friends magazine and a handful of originals written by Allcroft and director David Mitton. This meant episodes capturing Wilbert Awdry’s concerns with issues, for example, of steam railway preservation, drawn straight from the 1960s, coexisted with ones addressing new issues such as environmentalism.6

From Series 5, which aired in 1998, no more of the stories were based on the original Railway Series, being comprised mostly of Allcroft and Mitton originals, with a broader team of writers contributing from Series 6 onwards. This also involved the introduction of new characters, including female ones such as tender engine Emily, who first appeared in Series 7 in 2003, somewhat redressing the heavy gender imbalance of Awdry’s original cast of engines. There were also changes in the programme’s broadcasting with episodes now being shown in the UK on Nick Jr, although they also would for the remainder of the 2000s also return to ITV as well. Behind the scenes, the aforementioned 2002 sale of Gullane (formerly Britt Allcroft Productions) to HiT! also meant the latter were now responsible for producing the show, renamed Thomas & Friends.

From Series 8 onwards, following the departures of O’Donnell and Campbell, a new theme was introduced: ‘Engine Roll Call’, composed by Ed Welch. Piano-led as compared to the synth-heavy original theme, it nonetheless had a steady rhythmical pace that captured the tempo of the trains in motion. An instrumental version played over the programme’s opening credits as Thomas once again made his way across Sodor’s railway.

Before the closing credits, which also featured the instrumental, a version of the theme with vocals (sung by a children’s choir) would play over a sing-along section showcasing all of the main engines at work.

The lyrics were played along the bottom of the screen, further emphasising the intended routinised participatory sing-a-long nature of the segment:

They’re two, they’re four, they’re six, they’re eight

Shunting trucks and hauling freight

Red and green and brown and blue

They’re the Really Useful crew

All with different roles to play

Round Tidmouth Sheds or far away

Down the hills and round the bends

Thomas and his friendsThomas, he’s the cheeky one

James is vain, but lots of fun

Percy pulls the mail on time

Gordon thunders down the line

Emily really knows her stuff

Henry toots and huffs and puffs

Edward wants to help and share

Toby, well, let’s say, he’s squareThey’re two, they’re four, they’re six, they’re eight

Shunting trucks and hauling freight

Red and green and brown and blue

They’re the Really Useful crew

All with different roles to play

Round Tidmouth Sheds or far away

Down the hills and round the bends

Thomas and his friends

‘Engine Roll Call’ thus captured the individuality of the different engines, with their particular recognisable characteristics and traits (note the emphasis on the only female engine mentioned, Emily’s, competence), and their diversity within a collective unit that echoed Wilbert Awdry’s original books’ mantra about proving themselves to be ‘Really Useful Engines’ (though with a slight change of emphasis that made their usefulness a given rather than a constant aspiration).

Further changes were afoot with a switch to partial usage of CGI from Series 12 in 2008, undertaken by HiT subsidiary HOT Animation; and then from Series 13, broadcast in 2010, the show would be fully digitally animated, firstly by Vancouver-based Nitrogen Studios, and subsequently Toronto-based Arc Productions (later renamed Jam Filled Productions). The private equity firm Apax, which had bought HiT! in 2005, would in turn sell it its roster of programmes (which, as mentioned, also included Fireman Sam) to the entertainment arm of American toy manufacturer Mattel in 2012. Like Fireman Sam, Thomas & Friends was now also a component of Channel 5’s Milkshake compendium of children’s programming for UK audiences (though the programme had long been broadcast internationally, with different narrators and in different languages).

The roster of engines continued to expand, allowing for a broader range of toy versions of the engines to be sold. Moreover, it also allowed for the introduction of engines from other countries, such as Hiro from Japan, Millie from France, and Victor from Cuba, illustrating a commitment to ethnic diversity as well as greater gender balance (and increasing the appeal of the programme and toys to overseas markets).

Despite the introduction of CGI, however, the visual logic of how the engines on Sodor operated still adhered broadly to that of earlier series when physical models were used, even as they had drifted away from Wilbert Awdry’s firmer grip on the actual workings of railways (which was itself peppered with a higher proportion of accidents and unusual incidents, albeit often drawn from real life examples, than would occur on a real railway). This is encapsulated by the digitised version of the ‘Engine Roll Call’ sequence, which to all intents and purposes is pretty similar to the model-based one:

A more substantial shift, albeit along lines already anticipated in earlier changes, occurred in the wake of the 2018 feature-length film, Thomas & Friends: Big World! Big Adventures!. In this, Thomas accompanied an Australian rally car named Ace to take part in a multicontinental race, and ends up (via several ocean-crossing ship journeys) travelling through Africa, the Americas, Asia, and finally back through Europe to Sodor, joined by a Kenyan female engine, named Nia.

The ensuing final three seasons of Thomas & Friends persisted with this theme. These now two-part episodes divided the action between Thomas’s adventures working on other railways in faraway countries (such as Australia, Brazil, China, and India) and his escapades alongside a more gender-balanced and ethnically diverse set of engines (some older characters like Edward and Henry having been discarded). The earlier third-person narration was now dropped, with Thomas instead directly addressing the audience during interspersed segments with introductions and reminiscences that reinforced the main stories’ moral takeaways. CGI was now used to give a more fantastical element to the stories, whether to capture the characters’ more ridiculous daydreams, or more physically unrealistic passages of action, like Thomas somehow doing jumps at the beginning of every episode.7

These transformations were encapsulated by a new opening credits sequence, in which Thomas travelled at high speed in an almost hyper-real fashion between multiple settings across the globe, before eventually passing through a more abstract and colourful series of shots to eventually be shown racing around the Earth flanked by several of his other engine friends. This was accompanied by a new equally fast-paced theme, with a much rockier vocal over a guitar-heavy instrumental.

The breakneck pace was also captured lyrically, through repeated use of the word ‘go’:

James, Percy, Nia, and Gordon,

Rebecca, and Emily,

And Thomas number one!Let’s go, go, go

On a big world adventure

Let’s go, go, go

Explore with Thomas and his friends!

Let’s go, go, go

And meet new friendly faces

The world’s just a train ride away!Big world

Big, big adventures!

Thomas & Friends

Big World! Big Adventures!

There are two other striking elements. Firstly, that accelerated pace underlines the promise of globalisation, which had heavily underpinned the programme’s development over the previous three decades. These new series evoked a connected world in which Thomas could sample adventures all over the world and back in Sodor, although his missing home and his friends and encountering difference while overseas was also a recurring theme. It’s a vision that feels remarkably pre-COVID (not least the stories set in China), and it is perhaps apt that the final episodes were first broadcast in 2020. The second is that that opening roll call echoed the cultivation of a far more representative cast of characters than had previously been the case, and yet leant even more towards giving Thomas ‘Number One’ himself pre-eminence, as a unifying presence between different settings and as the character who directly addresses the programme’s audience.

These episodes would still often conclude with sing-a-long song sequences along the lines of ‘Engine Roll Call’; indeed some with a slightly updated version of exactly that song. Others, however, bore out the newer spirit of these episodes, albeit with a gentler pace and more pensive lyrics than the opening theme. ‘The Journey Never Ends’, for example, continues the globetrotting theme but over a more sedate Afropop tune and with lyrics that emphasise specificity rather than dissolution of place.

We’ll go to China, Australia, Spain, Peru! (Yeah!)

Kenya, Mexico, the whole world through!

Check out the pandas, koalas, kangaroos

With Thomas and his friends

The journey never ends (Let’s go!)

‘Let’s Dream’, meanwhile, is an almost Disney-lite number, whose celebration of daydreaming – that foolish pastime which so often preceded engines getting a comeuppance in the Reverend Awdry’s original stories – accompanies a compilation of scenes from the engines’ flights of fancy in the episodes.

Let’s go, let’s dream

Come along with me

The big world is calling

All aboard for a fantasy

The world’s full of wonder

There’s so much we can be

Thanks to imagination and curiosityWe could be in a movie

Where we save the day

We could speed through the ocean

On the sun’s yellow rays

We could ride a roller coaster

And laugh all the way

Together we can

Do a million great things

This was not quite it for Thomas & Friends, however: Mattel launched a two-dimensional cartoon version, Thomas & Friends: All Engines Go, of which there have been four series since 2021. It continued the tendency towards being less representative of anything like real engines, and in which virtually all the characters are far more child-like, both trends neatly captured in the show’s opening credits and theme.

In contrast to the globalising tendency of the late 2010s series of Thomas & Friends, All Engines Go rather demonstrated a trend of wholesale Americanisation. Indeed, whereas the CGI episodes of Thomas & Friends continued to be conceived and written in the UK even as they were animated in Canada, All Engines Go is made entirely in North America.

Rolling the end credits

There are a few different trends comparable across the development of these three series that their changing musical accompaniments epitomised, which hopefully will have already become clear to the reader over the course of this piece:

The fairly concrete ideas of public services and their operational realities represented in those 1980s series of Postman Pat, Fireman Sam, and Thomas the Tank Engine had all but dissipated in the versions that aired in the 2010s and beyond. That hardly uncoincidentally occurred against a backdrop of widespread privatisation and a transformation of the brand identities of organisations undertaking those services (whether public or private). We can hear reverberations of these changes in the closing theme of Postman Pat: Special Delivery Service, or the evocation of the ‘Rescue Team’ in the latest version of the Fireman Sam opening theme.

There was likewise a drastic transformation in these programmes’ protagonists, from ordinary and representative figures to extraordinary ones undertaking remarkable forms of work. ‘We all know that [Pat’s] the best’; ‘Cause [Sam’s] brave to the core’; Thomas going from chuffing along his branch line to a steadily paced instrumental to speeding around the world while ‘Let’s go, go, go’ is sung in the background. Again, this is in keeping with the neoliberalisation of public services and an accompanying mutation in conceptualising what a public servant is.

The programmes continued to also champion ideas of community and working together, however, while also presenting community as increasingly diverse and greater parity of gender roles within the world of work, as evident from ‘Engine Roll Call’, for example. Yet, whereas ethnic diversity and women’s work was evident from the very beginning with Fireman Sam, in Thomas & Friends it rather turned some of the assumptions underpinning the original Railway Series on their heads.

There is obviously a tension between 2. and 3. The hero-collective relationship was clearly a live one from the very outset in the transformation of The Railway Series into Thomas & Friends. The hegemony of certain liberal politics in British children’s programming and the commercial logic of an expanded fictional universe with more episodes, more characters who can be turned into toys, favours the collective even as hyper-individuality is also accommodated. ‘James, Percy, Nia, and Gordon, Rebecca, and Emily, and Thomas number one!’ indeed.

Underpinning all of this is the neither even nor uniform process of globalisation that is integral to this story. These were programmes that were made by writers and institutions with inherently regional or national associations. The BBC. S4C. The Church of England. Central Independent Television. They created fictionalised but resonant rural localities in the Lake District, Wales, and the islands of the Irish Sea.

Greendale, Pontypandy, and Sodor remain integral to those fictional worlds, yet the geographies of production and broadcasting they rest upon have wholly shifted. Fireman Sam and Thomas & Friends originated with public and private broadcasting companies respectively, but both ended up owned by the British-American conglomerate HiT! by the 2000s, and American toy and entertainment manufacturer Mattel in the 2010s.

Postman Pat remained at the BBC, by contrast, but like the other two has also long been marketed to an international audience as well as a British one, being re-dubbed into multiple languages and broadcast across different countries (and of course, Sam Tân was bilingual from the very beginning). Concentration and marketisation carry a logic of homogenisation of programme content, and we can certainly see that in these shows; but equally, in these series’ conception, adaptation, and reception, logics of localisation and diversification are also at play.

If you’ve enjoyed this post, please consider supporting my work by becoming a free or a paid subscriber to the newsletter. Paid subscribers are vital to me being able to continue producing and expanding this newsletter.

You can also support my work by making a one-off payment, at a price you consider affordable.

Otherwise, please show your appreciation by sharing this post more widely, and referring the newsletter to friends.

You might also enjoy these posts from the Academic Bubble archive:

Troublesome Engines (1950)

The Rev. W. Awdry’s Troublesome Engines centred on a Christianised notion of moral economy, in which industrial action was pitted against unitary righteous authority.

The Three Railway Engines (1945)

The first book in the Reverend Awdry’s Railway Series sketched out a world of living engines, existing in relation to humans and rolling stock, governed by a clearly Christian moral framework.

Postman Pat: Special Delivery Service (2008–2017)

The BBC’s readaptation of the adventures of Britain’s most famous fictional postman mirrored many concurrent neoliberal transformations of its postal service.

Apparently my preferred bedtime prayer in those early days was ‘God bless Mummy and Daddy and Postman Pat’, which is a whole different type of trinitarianism.

In ‘Froggy Fantasy’ (Ser. 9; Ep. 18), for example, Norman somehow sets fire to a swimming pool.

Bella Lasagne was written out of the show from Series 6 onwards, but brought back in 2016, midway through Series 10, assumedly as some sort of Brexit dividend.

For a full account of the Reverend Awdry’s life and the development of the Railway Series, see Brian Sibley, The Thomas the Tank Engine Man: The Story of the Reverend W. Awdry and His Really Useful Engines (London: Heinemann, 1995).

I still vividly remember as a ten-year-old watching this 1995 documentary in which the Reverend, by now in his mid-80s (he would die two years later), lambasted the newer episodes’ lack of fidelity to the actual workings of railways.

While ‘Based on the Railway Series by the Rev W Awdry’ appears on the screen, no less; clearly missing an ‘Incredibly loosely…’ from the beginning of that credit, and a ‘…who at this very moment is almost certainly spinning in his grave’ from the end.