The Three Railway Engines (1945)

The first book in the Reverend Awdry’s Railway Series sketched out a world of living engines, existing in relation to humans and rolling stock, governed by a clearly Christian moral framework.

Please support my work by becoming a free or a paid subscriber to the newsletter. Paid subscribers can access my full archive of posts at any time, and are vital to me being able to continue producing and expanding this newsletter.

This post is part of the ‘Rewound’ series of analyses of objects or episodes from cultural and political history.

The Three Railway Engines began life in 1942 as a single story about an anthropomorphised engine called Edward, told by its author, the Reverend Wilbert Awdry, to entertain his poorly infant son, Christopher. Christopher enjoyed it, and so his father came up with two more stories, involving two other engines, Gordon and Henry. Awdry was compelled to write the stories down to meet his son’s expectation of fidelity to their details as first told to him, and Wilbert’s wife Margaret thought them good enough to encourage him to try publishing them. Eventually the Leicester-based publisher Edward Ward bought the stories for a fee of £25. Ward decided he wanted to sell them as a single volume of four stories and commissioned Awdry to write an additional story that tied the previous three together, and so the first Railway Series book was published in 1945.1

The book opens with ‘Edward’s Day Out’, which tells the story of an engine named Edward who is picked on by other engines in his shed for being smaller than the others. However, Edward is given a chance to pull a train of coaches and despite being delayed by a missing guard, does well enough that he is promised he can go out again the following day. The second story, ‘Edward and Gordon’, begins with Edward being spoken to condescendingly by a larger engine called Gordon, whom he subsequently sees sulkily pulling a train of trucks while Edward is shunting. Gordon then gets stuck on a hill and Edward is needed to help push him up to the summit. Gordon does not so much as say thank you, but Edward is promised a new coat of paint.

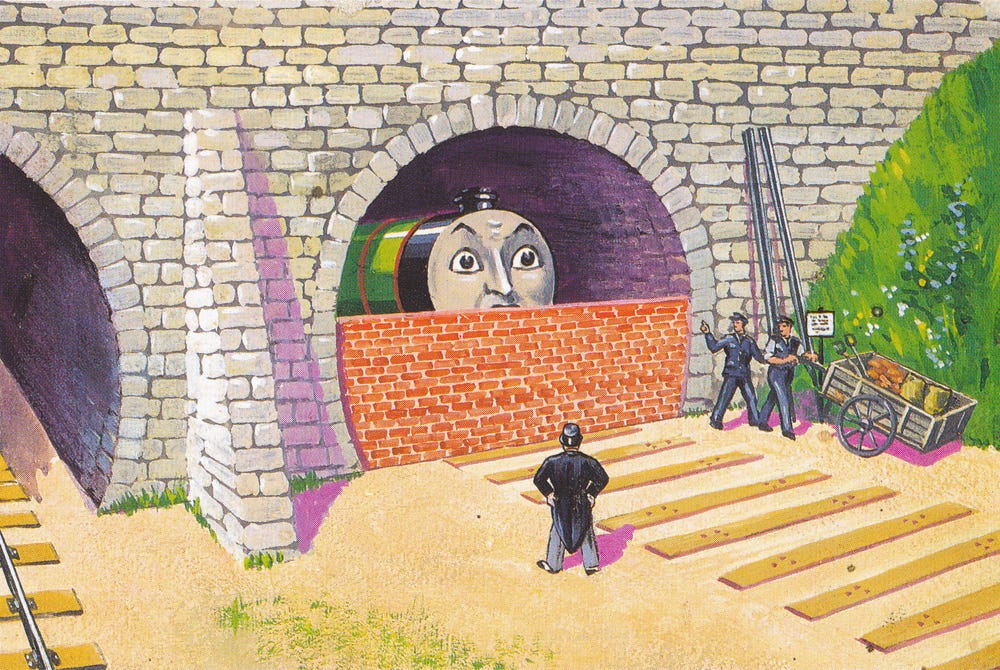

‘The Sad Story of Henry’ sees its eponymous engine character enter a tunnel while pulling a train and refuse to come out of it, for fear the rain would spoil his green paint. At the request of the ‘Fat Director’, who is aboard the train, the other passengers try to pull and then push him out of the tunnel, and then another approaching engine is tasked with pushing him out, but all to no avail. By way of punishment, the rails are removed, and Henry is bricked up in the tunnel.

The fourth and final story that Edmund Ward had specially commissioned Awdry to add is ‘Edward, Gordon and Henry’ and begins with Henry still trapped in the tunnel. Gordon, who is passing with the Express and takes pleasure in taunting Henry as he passes, suddenly suffers a burst safety valve. Edward is called upon to pull the train instead, but lacks the strength to do so. Gordon suggests letting Henry try, and so the Fat Director has the wall knocked down and an apologetic Henry successfully pulls the Express with Edward, before the two help Gordon back to the shed. The story and book ends with the three engines as good friends.

The book was crudely illustrated by the inexperienced William Middleton, based upon the Reverend Awdry’s initial rudimentary drawings. Middleton did a poor job of drawing the engines’ faces, as well as making a number of technical errors. Reginald C. Dalby, recruited to illustrate subsequent Railway Series books, was tasked with redoing Middleton’s illustrations for a new edition of The Three Railway Engines, and his illustrations have been used for all subsequent editions of the book.2

Animating engines

What I find particularly fascinating about The Three Railway Engines is that it is both an integral component of the canon Awdry would develop over the next 25 volumes, and a wholly fledgling piece of semi-accidental, ad hoc worldbuilding that nonetheless set the parameters he thereafter worked within. It is quite literally an act of incarnation, in which he made choices as to how to furnish these machines with spirit, personality, and agency. What did it mean to an Anglican curate for these trains to be alive, possessive of spirit? How did an ardent railway enthusiast square that with his own extensive familiarity with how engines actually worked?

In the first instance, what makes the engines clearly alive is that they express basic emotions in response to their circumstances as engines. In ‘Edward’s Day Out’, ‘Edward had not been out in a long time. He began to feel sad’.3 The other engines are ‘very cross’ when he goes out and they are left behind.4 Edward is ‘tired and happy’ after his sojourn.5 Awdry’s reimagining of the circular smokebox door at the front of a locomotive as a face was an effective visual means of communicating these emotions in a manner readily recognisable to children. This was the case even for Middleton’s mediocre illustrations, and more so in those of Dalby who, while not expert in the technical aspects of drawing engines, was adept at giving them childlike facial expressions.

The engines also express themselves verbally, their modes of speech often identified with the onomatopoeic descriptors of locomotive noises. Their dialogue likewise has the basic, repetitive, rhythmic flow of trains in motion, which is integral to the book’s appeal to young children:

“I can’t do it, I can’t do it, I can’t do it,” puffed Gordon.

“I will do it, I will do it, I will do it,” puffed Edward.

“I can’t do it, I will do it, I can’t do it, I will do it, I can’t do it, I will do it,” they puffed together.6

The sound of the engine, of the Reverend Awdry’s stories, is a basic sonic exemplar of what being alive is, as something akin to being a machine in operation.

Then there is the question of motion and agency. In ‘Edward’s Day Out’, for example, Edward is able to leave the shed because ‘…the fireman lit the fire and made a nice lot of steam. The the driver pulled the lever, and Edward puffed away’.7 The engine’s freedom to move is the gift of railway workers. Yet we also learn that Edward is gentle in approaching the coaches, and is credited with working hard. Gordon, by contrast, is accused by of not trying when he gets stuck on a hill in ‘Edward and Gordon’, while Henry can simply refuse to come out of the tunnel in ‘The Sad Story of Henry’. Mobility is a product of human-engine collaboration, immobility of engines not cooperating, and both are invested with a deep moral meaning.

Developing a taxonomy

This conceptualisation of the relationship between humans and engines would be further fleshed out in later books, but certain aspects are already evident here. Firstly there is something of a parent-child dynamic between them, with drivers and firemen delimiting the scope of engines’ behaviour, facilitating their freedom or denouncing their disobedience. However, the railway staff are also dependent upon these sentient forms of transportation who have an apparent degree of agency in whether or not to move, rendering the relationship more like that between humans and beasts of burden or riding animals. This also hints at another parallel in the human-engine dynamic, between management and labour. Viewing the latter relationship as approximate to parent and child or human and animal implies a steep but benevolent hierarchy that obscures the greater dependence of management on labour than vice versa.

Yet ironically, the most senior character in the book, the Fat Director (subsequently renamed the Fat Controller once the railways had been nationalised) is not yet the kindly but firm authority figure he would later evolve into. He is rather a figure of fun, who appears in the third story as a passenger on Henry’s train and who instructs the other passengers to try and pull and then push Henry out of the tunnel but does not join in, he claims, because his doctor has forbidden him from doing so.

The subcategorisation within the engine characters, such as the distinction between tender and tank engines which would become so important in Troublesome Engines some five years later, as I have written about here, is not yet a factor: the only engines in The Three Railway Engines are tender engines. But there is still an imputed hierarchy based on size, overturned when Edward is taken out of the shed, and later when Gordon’s safety valve bursts and the Fat Director blames it on his size: ‘I never liked these big engines – always going wrong.’8

A final component of the taxonomy in The Three Railway Engines is the rolling stock, animated in a far more limited way than the engines, and nowhere near as developed as would be the case in later books. The coaches, for example, are not individualised and explicitly gendered as in later books, where they are named and personified as work wives attacked to particular engines. Nonetheless, they are alive, possessing the ability to speak and feel:

“Be careful, Edward,” said the coaches, “don't bump and bang us like the other engines do.” So Edward came up to the coaches, very, very gently, and the shunter fastened the coupling.

“Thank you, Edward,” said the coaches. “That was kind, we are glad you are taking us today.”9

Trucks are also sentient and communicative, but clearly of a lower status and less meriting of consideration:

Edward liked shunting. It was fun playing with trucks. He would come up quietly and give them a pull.

“Oh! Oh! Oh! Oh! Oh!” screamed the trucks. “Whatever is happening?”

Then he would stop and the silly trucks would go bump into each other. “Oh! Oh! Oh! Oh!” they cried again.10

Gordon, meanwhile, views pulling goods trains as demeaning, and subsequently blames the trucks, who ‘hold an engine back so’, when he gets stuck on the hill.11 This comes across here as simply an excuse, whereas in later books it becomes clear that trucks can maliciously pull engines back or push them forwards.

A Christian moral world

We also see in The Three Railway Engines the initial construction of a Christian moral world in which virtue is always rewarded and sin punished, but not without the possibility of redemption. This would become the familiar formula of The Railway Series books, but it is worth noting that its initiation was at least partly an accident, in that while much of this was present in the narrative arcs of the individual stories, it was Ward’s decision to compile the stories into a single volume (and ask Awdry to write a fourth story for it) that gave a more systematic, all-encompassing quality to this worldview.

So, in ‘Edward’s Day Out’, Edward is bullied but then taken out of the shed (unlike the other engines who are now jealous of him), is both considerate and hard-working and is rewarded with the promise of being taken out of the shed again – work and its repetition being its own reward! In ‘Edward and Gordon’, Gordon is too proud and gets his comeuppance when he gets stuck on a hill, and then too stubborn to work hard to get over the hill; Edward works hard to the point of exhaustion to help Gordon over the hill, and while does not receive any gratitude from still too-proud Gordon, but is promised a new coat of paint by his driver. In ‘The Sad Story of Henry’, Henry’s vanity is the source of his downfall, which it is indicated (by use of the present tense) is the lasting, justified state of affairs:

So they gave it up. They told Henry, “We shall leave you there for always and always and always.”

They took up the old rails, built a wall in front of him, and cut a new tunnel.

Now Henry can’t get out, and he watches the trains rushing through the new tunnel. He is very sad because no one will ever see his lovely green paint with red stripes again.

But I think he deserved it, don’t you?12

‘Edward, Gordon and Henry’ draws these elements together and builds upon them. Gordon continues to be proud and to mock Henry in his predicament whenever he passes, but it is on one occasion when he is about to do this that his safety valve bursts. Yet Gordon’s offhand suggestion, after Edward cannot pull the Express, that Henry be given the opportunity instead, leads to the latter’s redemption. We are told at the beginning of that story that it was specifically the Fat Director who had had Henry shut up in the tunnel, and it is he who takes up Gordon’s suggestion and asks Henry to help pull the train. Henry and Edward work hard in combination, and when the Fat Director offers Henry a new coat of paint as reward, he chooses blue with red stripes to be like Edward, and subsequently continues to take pride in his appearance – but not so much as to prevent him from doing his work.

The takeaway message of The Three Railway Engines, and indeed of the other entries in the first half of the series (prior to their taking a somewhat darker tone as the threat of dieselisation and the end of steam came into their purview), was that this is a fundamentally providential world, in which good and bad deeds result in fairly swift and wholly just consequences, but in which also no one is irredeemable. This is in part the direct consequence of the engines’ choices and actions, but equally is facilitated and guaranteed by the kindness and authority of adult humans – initially in the personhood of the engines’ drivers and firemen, and then in the nascent higher authority of the Fat Director, who would come to universalise these rules in the running of the railway.

If you’ve enjoyed this post, you can show your appreciation by sharing it more widely, recommending the newsletter to a friend, and if you’d like, by buying me a coffee.

See Brian Sibley, The Thomas the Tank Engine Man: The Story of the Reverend W. Awdry and His Really Useful Engines (London: Heinemann, 1995), Ch. 5.

Ibid.

The Three Railway Engines (Leicester: Edmund Ward, 1945), p. 4.

Ibid, p. 8.

Ibid., p .16.

Ibid, p. 28.

Ibid, pp. 6–8.

Ibid, p. 52.

Ibid, p. 10.

Ibid, p. 20.

Ibid, p. 24.

Ibid, p. 46.