‘It Laughs with and at the English’

Passport to Pimlico’s contemporary reviews stressed the film’s qualities as a specifically national form of comedy, while also relishing its antiauthoritarian and anti-statist elements.

Please support my work by becoming a free or a paid subscriber to the newsletter. Paid subscribers can access my full archive of posts at any time, and are vital to me being able to continue producing and expanding this newsletter.

This post is part of the ‘Research and Reflections’ occasional series, consisting of pieces based on my ongoing academic research, as well as on my musings on and responses to current affairs and personal developments.

In my Rewound post on Passport to Pimlico (1949), published earlier this year, I remarked upon how the film’s retrospective reputation as a particularly whimsical, gentle Ealing comedy belied the ardently social democratic, anti-capitalist core especially evident in the more zealous first drafts of the film’s story, and still persistent in more muted form in the finished version of the film.

I want to pick up the thread again here, and explore how this toning down and shifting of emphasis continued through the film’s contemporary promotion and reception.

Promoting Passport to Pimlico

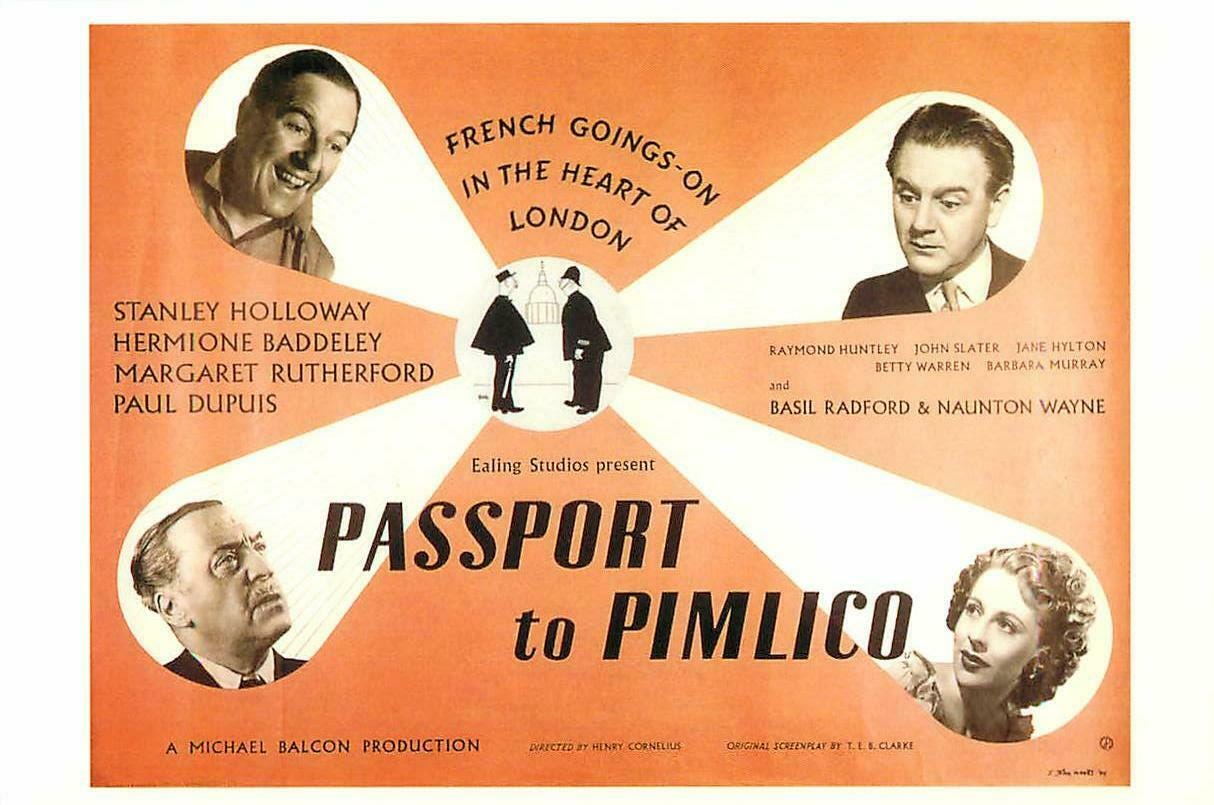

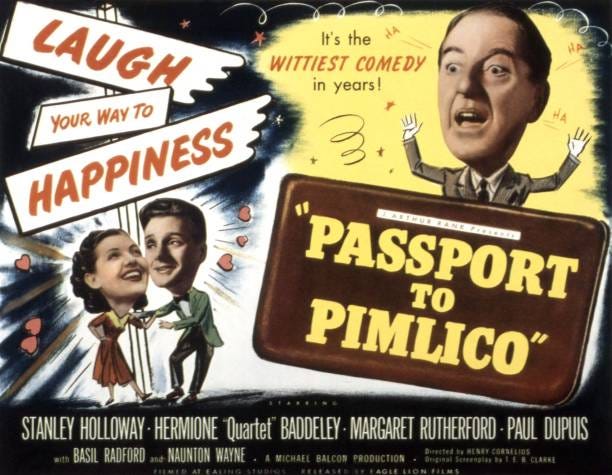

Ealing’s promotion of Passport to Pimlico’s went heavily on the comedy element, as with its posters featuring enlarged versions of the principal actors’ heads atop daintier cartoon bodies, and taglines designed to evoke expectations of amusement, such as ‘Laugh your way to happiness’, and ‘French goings on in the heart of London’ – the latter accompanied by a drawing of police officers in British and French dress encountering each other. French-ness here implied foreignness and exoticism, not resistance to an external occupier (which was an equally significant component of the idea of Burgundian Pimlico in the film.

The film and Ealing’s promotion of it certainly captured the domestic press’s, and it would also seem filmgoers’, imaginations. Reviews were uniformly positive, and in some cases mentioned the rapturousness of the audiences’ responses to it in cinemas. The film was a huge success during its three-week run at the Gaumont in Haymarket and at Marble Arch Pavilion, and was only taken off at the height of its popularity on May 18th due to other booking commitments.1 Industry publication Kine Weekly listed it among ‘Other Notable Attractions’ in its review of 1949’s biggest box office hits.2

Emphasis on Englishness

There were two especially dominant themes in the film’s reception. One was pride in it as a paradigmatic example of what English or British – the slippage between the two descriptors suggests a lack of distinction between the two in the minds of the London papers’ film critics – cinema was and should be. The Daily Express identified Connie Pemberton’s (Betty Warren) line ‘We are English – and it’s because we’re English that we must fight for our right to be Burgundians’ as the best line in the film.3 The quote was also included in a number of other reviews.4

More generally, reviewers also praised scriptwriter T. E. B. Clarke for the way he fleshed out the film’s fantastical comic scenario while rooting it in and satirising English life. Indeed, they drew an explicit connection between national identity, comedy, and quality. ‘It laughs with and at the English,’ remarked the Sunday Times.5 The Sunday Dispatch got even more local in its diagnosis: ‘The dialogue is neat and smacks of nowhere else but London in its style of humour.’6 Writing in the Sunday Express, Steven Watts praised Ealing for having ‘come closer to the heart and nature of the life of people in this country than anybody else’.7

This prompted a degree of bullishness in some quarters as to how good-quality British films could perform domestically and abroad if given the chance. Watts noted that Passport to Pimlico ‘has none of those big names, none of those big dimensions or “production values” which we have always been told are the only way to make even English-speaking foreigners look at our films.’ He added: ‘You don’t come away from this picture thinking of a star. I would be hard-pressed to tell you who is the star of the excellent team which shares the work’.8 The Daily Graphic railed against exhibitors and distributors for ensuring that foreign fare and ‘Wicked Lady type’ British films dominated cinemas rather than more authentically English films like this.9

The film’s brand of Englishness/Britishness did attract admiring reviews overseas. When Passport to Pimlico was shown at that year’s Cannes Film Festival, L’Espoir de Nice praised it as:

…really good cinema…The English film-makers merrily satirise their local governments, their diplomacy, their police methods. They manage to ridicule situations which ought to be dramatic, and it is curious to note that the English, who have suffered so terribly during the war, are capable of remembering its more painful moments in an atmosphere of fantasy.10

Le Figaro said of the film, ‘Sometimes the development is a little “far-fetched”, but mostly it contains witty situations in which one easily recognises the essentially British sense of humour’.11 The following month it played the Trans-Lux-60 Street Theatre in New York. The New York Post described it as ‘a kind of British humour that survives export more successfully than varieties based on dialect', while the New York Daily News called it a ‘diverting comedy. A clever satire on politics and international relations’.12

An anti-statist perspective?

The second dominant strand in Passport to Pimlico’s contemporary reception was its interpretation as, above all, a film opposed to statism and controls. The Sunday Dispatch noted with envy that the inhabitants of Miramont Place ‘can make their own laws, import what they like from across the border, abolish purchase tax, rationing, etc., and do exactly what you and I would like to do if we had half the chance’.13 In a similar vein, the Evening News remarked: ‘Imagine, if you can bear the painful thought, the unrestrained joy of these Pimlicans when they realise that all Whitehall’s orders in Council and forms in triplicate matter to them not a tinker’s cuss’.14 The Sunday Dispatch, meanwhile, asked its readers:

Now what would you do, citoyens, if you found that your own back alley was really a foreign country? Would you declare yourself an alien, no longer forced to suffer the kind of life imposed by Sir Stafford Cripps? Would you burn your ration book? Tear up your identity card? Abolish purchase tax? Forbid any cry of “Time, gentlemen, please!” at your local pub?15

These are, it ought to be stressed, extremely partial readings of a film whose cast of characters are ultimately compelled to implement their own, stricter controls in response to the constitutional crisis that befalls them. Yet that does not mean these reviews were wrong in perceiving vicarious pleasures to be had in those same characters’ earlier libertarian spasm, nor to highlight their anti-authoritarian streak – albeit one that sits alongside a desire for law and order – directed primarily against the national government.

The idiosyncratically socialist writer J. B. Priestley, who had worked with Ealing to adapt his own play They Came to a City for the screen in 1944, reviewed Passport to Pimlico for the left-leaning New Statesman. Priestley claimed that the audience at the Newport cinema where he watched the film ‘hilariously greeted’ its characters’ evasion of the restrictions placed upon them.16 Yet while critical of Labour for not jettisoning ‘Cumbersome and pedantic methods’ of government while expanding the state and its role, he insisted on perceiving nuance within the watching crowd’s mood:

Most people here are sensible enough to understand that in the situation we are placed in now many major controls are necessary. We have to discipline ourselves. I think many of the controls are enforced with foolish inflexibility, largely because minor officials lack either the power or the intelligence to make exceptions.17

This caveated critique of arbitrarily wielded overmighty power echoed the sentiments that Passport to Pimlico’s director Henry Cornelius expressed in an interview with the conservative-inclined Daily Graphic:

I am a timid man and in making “Passport to Pimlico” I wanted to get a message across to my fellow sufferers whose bones, like mine, turn to water when confronted with authority. If after seeing the film there is a bit of extra determination in the way in which they confront their boss, landlord or mother-in-law, then “Passport to Pimlico” has not been made in vain. Not that I am waging a campaign against these or any other reputable agents of authority. In fact, I am sure that many of the controls and restrictions facing mankind all over the world to-day are necessary and will ultimately help progress. But I am sure that we shall never get anywhere unless we constantly remind ourselves that all these frustrating limitations of freedom are man-made and if “they” can put them up “they” can, presumably, pull them down – and in this country “they” still means “us”.18

Priestley’s and Cornelius’s readings get closer, I think, to the contradictions and tensions that propel Passport to Pimlico forward. The film carries multiple impulses: to represent Britain, positively and enthusiastically; to champion communal welfare over individual self-interest and unrestrained capitalism; to thumb its nose at bureaucratic, top-down statism. Yet the economically liberal readings of it in the British press at the time are illustrative of why a film that offered a localised, autonomist vision of post-war social democracy has enjoyed such an enduring appeal across a broader political spectrum.

If you’ve enjoyed this post, you can also show your appreciation by sharing it more widely, recommending the newsletter to a friend, and if you’d like, by buying me a coffee.

You might also enjoy these posts from the Academic Bubble archive:

Passport to Pimlico [Pressbook] (1949), PBS-40842, British Film Institute Archive.

Kine Weekly (15 Dec. 1949).

Daily Express (30 Apr. 1949).

Evening Standard (28 Apr. 1949); Evening News (28 Apr. 1949); Sunday Pictorial (1 May 1949).

Sunday Times (1 May 1949).

Sunday Dispatch (1 May 1949).

Sunday Express (1 May 1949).

Ibid.

Daily Graphic (30 Apr. 1949).

Quoted in Passport to Pimlico [Pressbook] (1949), PBS-40842, British Film Institute Archive.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Sunday Graphic (1 May 1949).

Evening News (28 Apr. 1949).

Sunday Dispatch (1 May 1949).

It is worth noting here that Labour had won Newport from the Conservatives at the 1945 election and would hold it until the seat’s abolition in 1983.

New Statesman (16 Jul. 1949).

Daily Graphic (16 Jun. 1949).

Thank you for this analysis, Dion. I haven't heard of the film before but I'll try to check it out!