Passport to Pimlico (1949)

Passport to Pimlico is often seen retrospectively as whimsical, but drafts of earlier versions of the film demonstrate a more sharply political edge.

Please support my work by becoming a free or a paid subscriber to the newsletter. Paid subscribers can access my full archive of posts at any time, and are vital to me being able to continue producing and expanding this newsletter.

This post is part of the ‘Rewound’ series of analyses of objects or episodes from cultural and political history.

Spoiler alert: This analysis of the film A Family Affair and its themes reveals plot details for the purpose of enhancing that analysis.

Passport to Pimlico, with its famed scenario of an inner London neighbourhood suddenly finding itself independent from the rest of Britain, is today remembered as a canonical British film. It is also generally regarded as representative of a wider canonical subgenre of ‘Ealing comedies’, made at Ealing Studios during the 1940s and 1950s, with their subtle, situation-centred humour, wryly drawn characters, and whimsical scenarios.

This is a characterisation that some scholars have challenged. Most notably, as I wrote about in this earlier post, the film critic Charles Barr rejected the Ealing comedy category as the best framework for understanding the films included in it. Rather, he split them within two broader tendencies in Ealing’s post-war output: the gentler mainstream, epitomised by the films written by Passport to Pimlico’s scriptwriter, T. E. B. Clarke; and the more acerbic, unsentimental films made by the likes of Scottish-American director Alexander Mackendrick. Barr interpreted Passport as embodying Clarke’s work: a fantasy in which characters respond to harsh post-war realities by retreating into a safer world of remembered wartime unity.1

I want to push back somewhat against both these readings. Having looked through files relating to the film’s production in the British Film Institute’s ‘T. E. B. Clarke collection’, I found a much more zealous edge in Clarke’s early iterations of the story, which were subsequently softened as it was developed into the film itself. In this post, I want to trace the evolution of the film’s ideological inclinations, and their relationship to the broader industrial and socio-political context in which it was made.

Ealing Studios

Film production had taken place at Ealing in West London since the early twentieth century. The current studios were built there in 1931, with Michael Balcon taking over as studio head in 1938, following a difficult spell at MGM’s British subsidiary studio. Under Balcon, Ealing geared towards a sustainable roster of good-quality, commercially viable productions, facilitated by a distribution deal with the Rank Organisation. This enabled the studio to survive for a time amid declining conditions in the British film industry, with the Ealing team continuing to make and release films until 1958 (its studios having been sold to the BBC three years earlier).

Balcon wanted to make films that provided a positive representation of Britain as a bastion of liberal democracy, community, and fairness.2 He fostered a working environment in which talented, in-demand staff sacrificed the higher salaries they could have gained elsewhere for the promise of greater security, opportunities for career development, and the maintenance of their artistic integrity. Film production at Ealing was remarkably collective, with decisions made through ‘round table’ discussions in which all creative staff could contribute ideas to films they were not directly involved in – though Balcon remained the key gatekeeper within this system.3

Under Balcon, Ealing’s wartime films had focused heavily on the representing collective service and sacrifices the conflict entailed, and these conventions remained strong into peacetime. From the late 1940s, Ealing became well known for comedies such as Passport to Pimlico (1949), Whisky Galore! (1949), Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949), The Lavender Hill Mob (1951), The Man In The White Suit (1951), and The Ladykillers (1955). Yet Ealing also turned out numerous critically and commercially successful dramas during this period as well, including It Always Rains on Sunday (1947) and The Blue Lamp (1950), made by many of the same creative personnel as who worked on the comedies.

Passport to Pimlico

Passport is set in the fictional neighbourhood of Miramont Place in Pimlico, in central London. There is an atmosphere of ill-tempered lethargy evident amongst the local populace at the start of the film, with the community having become stagnant, and its members’ lives unfulfilled. When local policeman Ted Spiller (Philip Stainton) goes to inform local shopkeeper and former air raid warden Arthur Pemberton (Stanley Holloway) of the forthcoming detonation of a nearby unexploded bomb, he remarks, ‘It seems funny, Arthur, having to come and tell you about a bomb.’

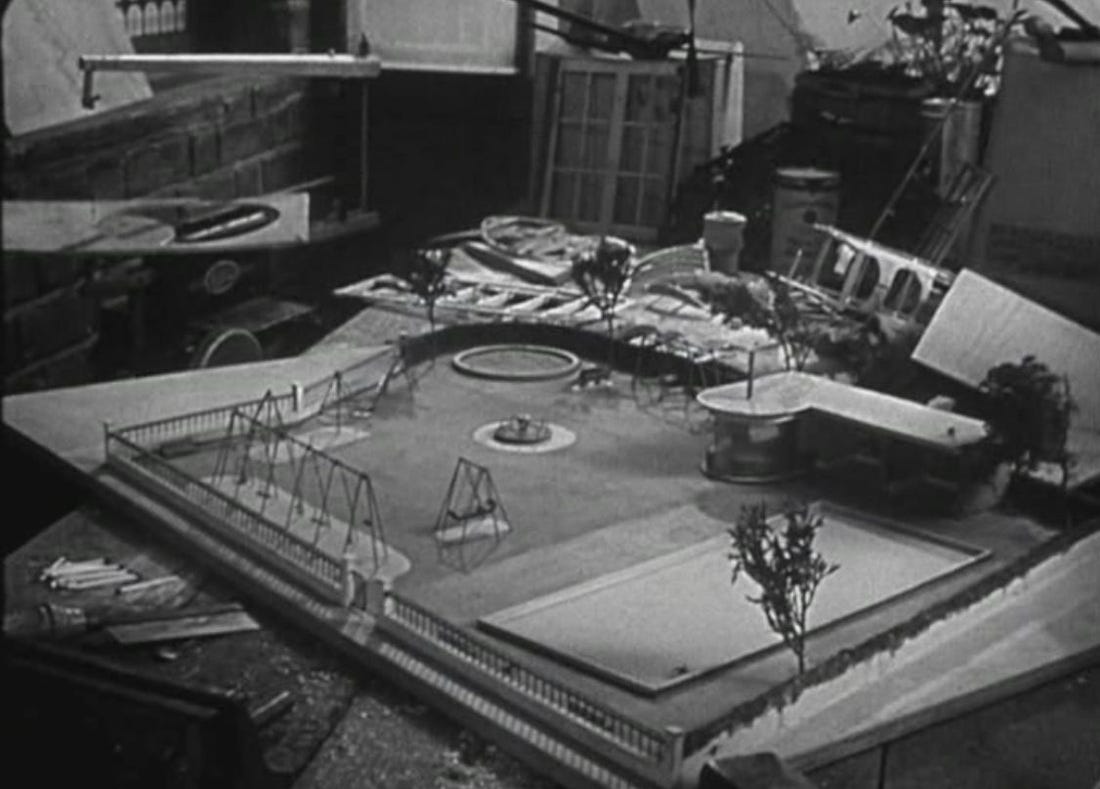

According to the film’s shooting script, Arthur is ‘the local “character”, and nearly everyone likes and respects him’.4 His current pet project, we learn, is to turn the local bombsite into a communal swimming pool and play area. He runs the shop with his wife, Connie (Betty Warren), described in the shooting script as ‘A country woman [who] finds her escape from the drabness of Pimlico in cultivating pot plants of all kinds’, and young adult daughter, Shirley (Barbara Murray).5

The Pembertons’ neighbours, meanwhile, are frustrated in their daily routines by rationing and bureaucracy, and through pursuing aspirations that seem beyond their reach. Fishmonger’s assistant Molly Reed (Jane Hylton) visits the shop of Edie Randall (Hermione Baddeley) to buy a dress, but is thwarted because she does not have enough coupons to do so. Then Edie is herself irked when PC Spiller informs her that she will have to ‘take a walk’ because of the detonation. She retorts, ‘I suppose they couldn’t make it early closing day…wouldn’t upset trade enough.’

Molly’s and Edie’s dissatisfaction is also a product of their yearning to be something that they are not (in ways that are heavily gendered). The film’s script described Molly as ‘a would be glamorous girl…who is no longer herself’.6 It characterised Edie as ‘a woman in the early forties who makes pathetic attempts to keep abreast of modern styles, but it seems a pity that she tries, for she hasn’t the taste to see that smartness cannot be acquired by a slavish adoption of “What is being worn” without any consideration for the age or figure of the wearer’.7

Similarly, the local bank manager, Mr Wix, is berated early on in Passport by a representative of head office, for an excessive display of autonomy in his handling of his branch. The script said of the incident that ‘Wix dreams of being an important person in the world of finance, but lacks the guts even to put up a show against his own immediate superior when reprimanded, as now, for exceeding his very limited powers’.8

The local council meets to discuss what to do with the bombsite, once the remaining bomb has been destroyed. Most of those at the meeting, including Wix, vote against Arthur’s lido idea. Yet as pompous council leader Mr Bassett (Arthur Howard) draws up the advert to sell the land instead, local children accidentally set the unexploded bomb off. When the adults arrive to make sure the children are unharmed, Arthur accidentally falls into the bomb crater, and before he can be lifted out, thinks he sees some gold coins. He and Shirley re-enter the pit that night and find treasure, along with a manuscript.

At the subsequent inquest, medieval historian Professor Hatton-Jones (Margaret Rutherford) reveals that according to the manuscript, the unearthed treasure and the land around it belonged to Charles the Bold, the last Duke of Burgundy, who secretly resided there after being assumed killed in battle at Nancy in 1477. Miramont Place is therefore Burgundian territory and the treasure belongs to the community in trust.

The significance of the situation dawns upon residents like Wix and Edie, who realise that they can now run their businesses as they see fit, without outside intervention. Yet the downside of this is that black marketeers also rush in to take advantage of the lack of regulation. The government, represented by civil servants Straker (Naunton Wayne) and Gregg (Basil Radford), seal off the enclave. Aided by the arrival of the Duke’s contemporary successor, Sébastien de Charolais (Paul Dupuis), the residents form a privy council – in line with historical Burgundian custom – comprising Arthur, Edie, Ted, and Wix, to govern the territory in the interim.

The government’s heavy-handed, officious manner, and disagreement over what should be done with the treasure, frustrates and alienates the Pimlico-Burgundians. The situation deteriorates, and supplies of water and electricity to Miramont Place are cut off. The residents respond by evacuating their children, and imposing a stricter internal rationing regime, including communal eating.

Determined that the treasure should be used for the rejuvenation of the district rather than simply handed over to the government, a greater sense of purpose and togetherness emerges amongst the new Burgundians. In Wix’s own words, he and Arthur have overcome ‘our early differences, and today in Burgundy we are absolutely unanimous in our resolve to keep our treasure’. Other characters such as Molly likewise find contentment in new official roles in Burgundy’s governance.

When a sortie to turn the water back on accidentally results in their food store being flooded, it seems that the Burgundians will be forced to cede. Yet an impromptu donation of food by sympathetic onlookers spirals into a huge citywide scheme to supply the residents of Miramont Place. Meanwhile the Privy Council progress both with the construction of Arthur’s lido scheme, while negotiating from their stronger position with the British government.

Eventually Wix comes up with a solution regarding the treasure, which will remain in trust of the residents of Miramont Place, who in turn loan it to the British government. The neighbourhood is finally reintegrated back into Britain on its own terms, symbolising the victory of its values. Passport concludes with a banquet by the lido, at which Ted distributes new ration books, remarking to Connie that ‘I never thought anybody would be pleased to see these things again’. She responds, ‘You never know you’re well off till you aren’t.’

Earlier iterations

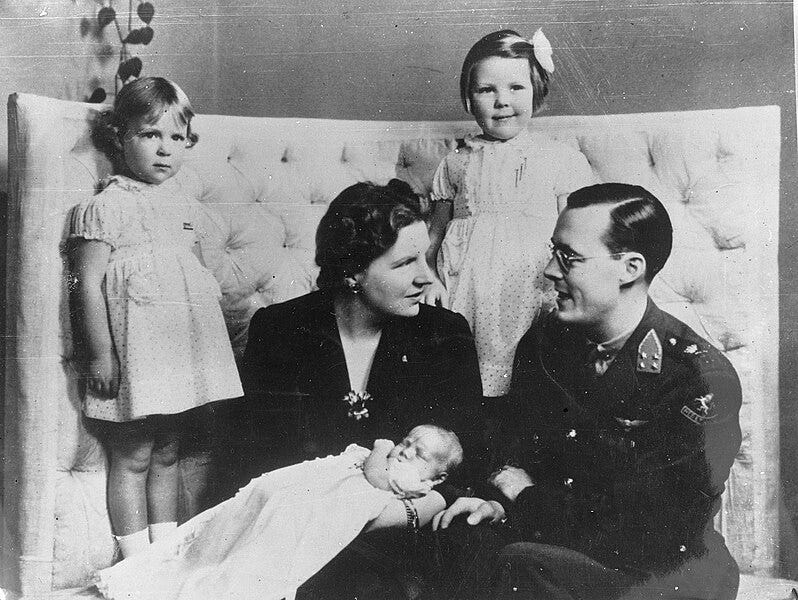

In his 1974 autobiography, Clarke claimed to have derived his inspiration for Passport to Pimlico from a wartime incident, when Princess Juliana of the Netherlands was due to give birth in exile in Canada. As the expected child could only potentially accede to the Dutch throne if born in the Netherlands, the Canadian government agreed to temporarily make her maternity ward Dutch territory. According to Clarke, he subsequently researched this aspect of international law and found it had once been quite common practice.

Clarke sought out an ideal expired state that could theoretically have held such an enclave in Britain, and settled on Burgundy, on account of the rumours and uncertainties surrounding Charles the Bold’s death. Satisfied, following discussion with director Henry Cornelius, that this scenario had great comic possibilities, they pushed ahead with the project.9

This may well have been how Clarke settled on this particular plot device, but the first outline he produced of Passport to Pimlico in 1947 seemed little concerned with opportunities for humour. In this version, the protagonist was called ‘Councillor Jack Hulbert’. At a council meeting, Hulbert calls for a youth centre to be built on the local bombsite, rather than a factory.

He points out that they have a shocking record here of juvenile delinquency and accidents involving children, simply because the youth of the neighbourhood have nowhere but the streets and the bomb ruins in which to play…Outside in the area under discussion children are fighting, kicking tin cans around, risking their lives in ruin-climbing expeditions, flinging mud at passing cars, and indulging in orgies of destruction.10

Following the bomb’s explosion, and the revelation about the area being Burgundian territory, Hulbert continues to strive for the creation of the youth centre, but is blocked by the area’s more ‘commercially-minded’ inhabitants. These include his opponents on the council, who open ‘gambling hells and [sell] whisky…at all hours of the day and night’. At a new borough election following the resolution of the crisis, ‘Hulbert and his supporters are returned, the knaves of the old council are out’. The film was to end with ‘a final shot of the Youth Centre in successful existence – the Union Jack flying at one end of it, the standard of Burgundy at the other’.11

The second treatment introduces the now renamed Pemberton: ‘When we learn that he used to be the chief air raid warden and that he now sits on the Pimlico Borough Council, we ought to get the feeling that we half-knew these things already, so obvious a choice does he seem for either function’.12 At the council meeting, he rallies against the fact that there is ‘No green space of any kind’ in this ward, and after the bomb goes off, ‘instinctively reassumes his old blitz-time authority’.13

Later on, when a cosmetics manufacturer named Crowley persuades Bassett to let him take advantage of the lack of restrictions in the new Burgundy to build a factory on the bombsite, Pemberton and his daughter are indignant. She tells Bassett, ‘I don’t see the Council have any right to sell that land without consulting the people who were born in the neighbourhood. It’s our property, and we can find plenty of better uses for it than handing it over to the Black Market’.14 Mr Pemberton subsequently leads an angry crowd of residents to the site, frightening Bassett and Crowley away.

We get some sense of the transition between these early versions of Passport to Pimlico and the finished film from a collated set of notes on different versions of the script from 1948. It is not clear who had written what, but it is evident from them that Clarke’s story evolved through the collective process of feeding back on film projects as they developed. One comment, for example, stated: ‘I feel now that Arthur’s insistency on the swimming pool idea should be more personal, more his pride in his model and less of the priggish emphasis on the communal and social welfare scheme.’15

Throughlines

The whimsically comical aspect of Passport to Pimlico seems to have been a subsequent appendage to the project, rather than there at its origin. It is worth remembering that the Ealing comedy did not really exist a subsection of the studio’s output at the point it was being made. The first film that might be classified as such, Hue & Cry – which Clarke had also scripted – was only released in 1947, the same year as Clarke also began developing Passport. However, Passport’s release was followed shortly by two more comedies, Whisky Galore! (in June 1949) and A Run for Your Money (in November), suggesting its original story may have been filtered through a new zeitgeist at the studio that Clarke was himself integral in developing.

It is very much in keeping with this interpretation that the first person asked to play Arthur Pemberton was not Stanley Holloway, but Jack Warner, whose acting style was avuncular but much less broad.16 Warner had already played tough but kindly Corporal Horsfall in Ealing’s 1946 prisoner-of-war drama The Captive Heart, and although his next few roles in films made by the studio were against type as either more cynical or downright treacherous figures, he would again channel Horsfall in his career-defining role, as PC George Dixon in The Blue Lamp (also written by Clarke). It makes sense to read Pemberton, as initially conceived, as part of a continuum between Horsfall and Dixon.

This relates to the fact that Pemberton was a more explicitly political figure from the outset in the earlier versions of Passport to Pimlico. In these, he was a councillor from the outset, rather than simply someone who rose to the position of ‘Prime Minister of Burgundy’ as part of the film’s transformative fantasy. This aspect was deliberately toned down in the final film, along with his motivation to build the swimming pool (previously a youth centre) as an explicitly social democratic, anti-capitalistic endeavour.

It is also evident that Passport to Pimlico in its earlier iterations was also more explicit about the radicality of its vision of democracy. This is not one in which the political face of capital, as typified in the film itself by Wix, can be brought into a broad coalition to serve in the communal interest. It is one in which they are all voted off of the council in the original outline, or chased away by a crowd led by Pemberton in the first script.

This is not to suggest that it was simply progressive aspects of Passport’s initial design that were watered down in the finished film. Those older versions were also more explicitly concerned with juvenile delinquency, in a way that also typified a law-and-order, paternalistic liberalism evident in later dramas like The Blue Lamp. This may seem to bear out Barr’s charge that Clarke’s comic and drama films ought to be banded together as part of a benevolent, daydreamlike Ealing mainstream. Yet I counter that Passport to Pimlico also had a more overtly ideological core, which engaged seriously with questions of political change as vehicle for social transformation, even if the conventions of film as a medium and comedy as a genre ultimately partly masked that.

If you’ve enjoyed this post, you can show your appreciation by sharing it more widely, recommending the newsletter to a friend, and if you’d like, by buying me a coffee.

See Charles Barr, Ealing Studios (London: Charles & Tayleur, 1977).

Balcon outlined his approach to filmmaking during this period in a number of publications, including:

Michael Balcon, Realism or Tinsel: A Paper Delivered by Michael Balcon Production Head of Ealing Studios to the Workers Film Association at Brighton (London: Workers Film Association, 1943).

Michael Balcon, ‘Let British Films be Ambassadors to the World: A Cogent Plea from the Head of Ealing Studios’, Kinematograph Weekly, Vol. 335, No. 1969 (11 Jan. 1945).

Michael Balcon, The Producer (London: British Film Institute, 1945).

For an account of the film production process at Ealing, see Lindsay Anderson, Making a Film: The Story of ‘Secret People’ (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1952).

‘Passport to Pimlico: Second shooting script’, p. 10. SCR-13935, British Film Institute Special Collections.

Ibid., p. 11.

Ibid., p. 2.

Ibid., p. 6.

Ibid., p. 9.

T. E. B. Clarke, This Is Where I Came in (London: Michael Joseph, 1974), pp. 159–160.

‘Passport to Pimlico: Story outline with second treatment (19 Dec. 1947)’, p. 1. Box 1, Item 1.a), T. E. B. Clarke Collection, British Film Institute Special Collections.

Ibid., p. 6.

Ibid, p. 13.

Ibid, pp. 17, 19.

Ibid., p. 38.

‘Passport to Pimlico: Loose script pages in folder marked ‘Revised draft script 14.5.1948’, etc.’, p. 3. Box 1, Item 1.b), T. E. B. Clarke Collection, British Film Institute Special Collections.

Jack Warner, ‘Evening All (London: Star Books, 1979), p. 127.

That's really interesting to read. I grew up on a lot of these films - Saturday and Sunday afternoon films on the tv! Plus my mum was born in 1931 so she had seen these movies at the cinema on release. The films are a lot more nuanced than some of the categorisation of them that has been popular in film study circles. Thank you for sharing the I sights from the development of this project.