Double Jeopardy and Cold Cases

The murder of Stephen Lawrence inspired a rule change that eventually helped convict one of his killers; the process also revealed much about the British state’s relationship to historical injustice.

Please support my work by becoming a free or a paid subscriber to the newsletter. Paid subscribers can access my full archive of posts at any time, and are vital to me being able to continue producing and expanding this newsletter.

This post is part of the ‘Research and Reflections’ occasional series, consisting of pieces based on my ongoing academic research, as well as on my musings on and responses to current affairs and personal developments.

Content warnings: Anti-Black racism; Murder; Child loss; Bereavement; Sexual violence.

In this post, I want to discuss one way in which the past has been understood and deployed in the context of the English and Welsh legal system: namely cold cases, and – more specifically – how they functioned in the wake of the Criminal Justice Act 2003. That Act, among other things, provided an exception to the ‘double jeopardy’ rule, meaning that in certain circumstances, someone acquitted of a crime could henceforth be retried for the same crime.

To this end, I’ll look at the introduction of that piece of legislation, and how it eventually enabled Gary Dobson to be successfully re-tried in 2011 for the crime that originally spurred the rule change: the racist murder of Black teenager Stephen Lawrence in 1993.

What I especially want to concentrate on here is the way in which the law change enabled a judge to re-evaluate an instance of what was widely seen to be a major historical injustice, where the injustice was doubled by the failings of the criminal justice system, and in the process try to partly rehabilitate that same system.

Cold cases

Cold cases involve reopening filed unsolved cases to try and solve them based on new evidence or methods. This is not in itself completely novel, but the term itself is, originating in the US but subsequently migrating into British vocabulary as well. It pertains especially to the increased number of cases the police reopened in the early 21st century with the aid of substantial advancements in forensic science, rendering solvable crimes that previously seemingly were not.1

Martin Innes and Alan Clarke have asserted that cold cases are a form of retroactive social control. They exert that control firstly over what is collectively remembered, and in the process are then able to enact a greater degree of control in the present. Cold case review conferences are multidisciplinary affairs, bringing together different bodies of expertise to retrieve evidence and establish new facts, so that existing narratives to be deconstructed and new ones compiled.2

We might see this in part as a product of what Ian Waters has described as a partial transition from a modern to a postmodern system of policing, in the face of growing social diversity and fragmentation. In these conditions, the police’s and indeed the state’s, authority is no longer universally recognised, and it thus needs to adapt accordingly to different situations.3

Cold cases also rely on a symbiotic relationship between the police and the media. The media provide a useful vehicle for accruing new information, including on murder-anniversaries that offer opportunities to renew calls to the public for information, although inaccurate or inappropriate reporting can by contrast be detrimental to investigations.

Indeed, beyond the world of policing itself, the idea of the cold case has gained greater cultural resonance, aided by new forensic science-oriented dramas on both sides of the Atlantic. This genre taps into concerns about violent crime and the need to bring offenders to justice, as well as a fascination with recent advances in science, and the idea that the human corpse can function as a bearer of historical narrative.4 It is typified by Waking the Dead, a BBC drama series that ran between 2000 and 2011, about a cold case team operating on the margins of the police force, and often in opposition to vested interests within the establishment.

The murder of Stephen Lawrence

Stephen Lawrence was born in 1974 to Jamaican parents Doreen and Neville and grew up in Plumstead in Southeast London. On the night of 22 April 1993, while waiting for a bus in Eltham with his friend Duwayne Brooks, also of Jamaican heritage, Lawrence was subjected to racist slurs and then set upon and stabbed multiple times by a group of white youths. He and Brooks fled from the scene, but Lawrence subsequently collapsed and bled to death.

In wake of the murder, five suspects were soon identified: Gary Dobson, brothers Neil and Jamie Acourt, Luke Knight, and David Norris, all of whom had previously been involved in racist attacks in Eltham. They were not arrested and charged until May and June, however, and the Crown Prosecution Service subsequently dropped the charges in July. It deemed the identification of the five alleged perpetrators by Duwayne Brooks to be unreliable, a decision it repeated the following year after a Metropolitan Police Service review.

Lawrence’s family initiated a private prosecution in September 1994 against the five men, although the charges against Jamie Acourt and David Norris were dropped before the trial due to a lack of evidence. The remaining three were tried but acquitted in April 1996, after the presiding judge again deemed Brooks’ identification of the men inadmissible.

The resumed inquest into Lawrence’s death took place in February 1997, at which all five of the original suspects refused to give evidence on grounds that they could self-incriminate themselves. The jury subsequently recorded a verdict of unlawful killing ‘in a completely unprovoked racist attack by five white youths’.

Following Labour’s victory in that year’s general election, new home secretary Jack Straw launched an inquiry in July 1997 – in response to a request by Doreen and Neville Lawrence – into ‘matters arising from the murder of Stephen Lawrence’, under the chairmanship of retired judge Sir William Macpherson. The inquiry heard statements from 88 witnesses and examined over 100,000 pages of reports, statements, and other written or printed documents, before publishing its report in 1999.

The Macpherson Inquiry identified multiple failings in the Metropolitan Police’s handling of the murder and the ensuing investigation, including failing to deliver first aid to Lawrence at the scene, its chaotic initial response to the murder, the liaison team’s mishandling of the Lawrences, and the errors of senior officers during the investigation, including delaying unnecessarily in arresting suspects and failing to follow leads or obtain evidence from witnesses.

It concluded that this was in part the result of institutional racism, including the mistreatment and misrepresentation of Brooks and the Lawrences, the failure of many senior officers to accept this was a purely racially motivated killing, and broader displays of racial insensitivity.

The report also made multiple recommendations, including on improving police relations with ethnic minority communities; better practice for recording, investigating, and prosecuting racist incidents; improving recruitment of ethnic minority officers and diversity training within the police force; and wider initiatives for tackling racism including through school education.

Most significant within the present context of this post, it also highlighted that the status quo under common law, whereby no one might be tried twice for the same crime, posed a serious barrier to the possibility of justice ever being realised in this case:

If, even at this late stage, fresh and viable evidence should emerge against any of the three suspects who were acquitted, they could not be tried again however strong the evidence might be. We simply indicate that perhaps in modern conditions such absolute protection may sometimes lead to injustice. Full and appropriate safeguards would be essential. Fresh trials after acquittal would be exceptional. But we indicate that at least the issue deserves debate and reconsideration perhaps by the Law Commission, or by Parliament.5

Revising double jeopardy

In line with the report’s recommendations, Straw instructed the Law Commission to consider the ‘double jeopardy’ aspect of the law and make recommendations. The Commission reported back in May 2001, concluding that an exception should be made to the double jeopardy rule in the event of murder or reckless killing, where new compelling evidence was available to the prosecution.

The Labour government, following a second successive landslide election victory in 2001, published a new white paper in 2002, Justice for All. Citing the conclusions of both the Macpherson Inquiry and the Law Commission report, the white paper included a provision that the exception to double jeopardy be available on all serious crimes (including rape and armed robbery).6

It advocated that, in the event new evidence not conceivably available in the first trial comes to light, which strongly suggested the guilt of the acquitted defendant, the Director of Public Prosecutions could apply to the Court of Appeals to quash the acquittal. The court were instructed to do so if it also found the new evidence convincing and deemed it right a retrial should take place.

Justice for All formed the basis of the Criminal Justice Act 2003. This clarified that the Director of Public Prosecutions could apply for a retrial of acquitted suspects in cases involving ‘offences against the person’ (that is, attempted, solicited, or actual murder, manslaughter, or kidnapping), as well as severe sexual, drugs, criminal damage, and terrorist offences.

For the Court of Appeal to quash the acquittal, it had to be satisfied that two conditions were met. Firstly, it was presented with evidence ‘not adduced in the proceedings in which the person was acquitted’, and compelling in that it was ‘reliable’, ‘substantial’, and ‘highly probative of the case against the acquitted person’.7 Secondly, it deemed it ‘in the interest of justice’ for a retrial to take place, a decision it was to make based on its considerations of:

the possibility of the retrial being fair.

the duration of time passed since the offence was allegedly committed.

whether the evidence could conceivably have been presented at the original trial ‘but for a failure by an officer or by a prosecutor to act with due diligence or expedition’.

whether there has been such a failing since the trial.8

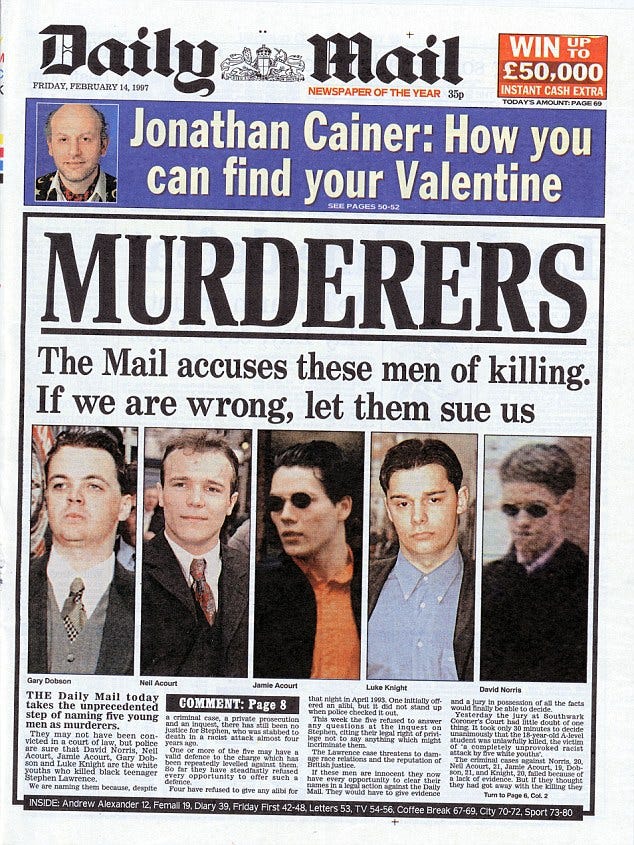

This law change was fuelled by two conceptions of injustice that the murder of Stephen Lawrence fed into. The first is one rooted in an objection to inequality, as experienced particularly by racialised minorities, and which strongly resonates on the left. The second is one that objects to actions not having consequences, to evil being done and not being punished, and which typically has a right-wing populist appeal, as evinced in the Daily Mail’s famous 1997 front page branding the five men accused of killing Lawrence as ‘MURDERERS’.

Labour sought to straddle and channel both. It went into the 2001 general election vowing to reduce crime ‘by dealing with the causes of crime as well as being tough on criminals’, with outline proposals designed to expedite the criminal justice process, increase the efficacy of punishment and rehabilitation of offenders, and better support victims. The exception to double jeopardy in certain cases was part of a much broader act generally in line with those ambitions, including expanding aspects of police powers, increasing admissibility of evidence of bad character, and stiffening sentences for more serious crimes.

Yet the rule change’s origin in the Macpherson Report is also hugely significant. All but three of its 70 recommendations were implemented over the next decade, including reforms addressing institutional racism in British policing. These formed part of a wider set of policies designed to tackle racism and racial inequality in the UK over the next decade, including the Race Relations Act (Amendment) 2000, Equality Act 2006, and Equality Act 2010.

The exception to double jeopardy was not introduced simply with the aim of eventually bringing Stephen Lawrence’s murderers to justice, but that was the paradigmatic example of historical injustice it was framed in response to.

R v Dobson

In 2006, the murder of Stephen Lawrence was one of several unsolved crimes subjected to a cold case review utilising new methods, undertaken in this case by LGC, the former Laboratory of the Government Chemist privatised in 1996. New lines of investigation eventually culminated in the identification of potentially incriminating evidence against David Norris, at that point in time already serving a jail sentence for drug dealing, and Gary Dobson. The latter had been acquitted of the murder in 1996, meaning then Director of Public Prosecutions, Keir Starmer, had to request that the Court of Appeal quash that original verdict.

The Court heard the case of R v Dobson in April 2011, with the Lord Chief Justice Baron Igor Judge presiding, with Mark Ellison as Queen’s Counsel representing the Crown Prosecution Service, and Timothy Roberts as Queen’s Counsel responding for Dobson, with the judgement handed down the following month. In it, the Lord Chief Justice laid out the details of the crime itself, asserting that ‘The murder of Stephen Lawrence, a young black man of great promise, targeted and killed by a group of white youths just because of the colour of his skin, scarred the conscience of the nation’.9

He then laid out the process by which Dobson and the others had been arrested but not charged following two successive Metropolitan Police investigations, and then how he, Neil Acourt, and Luke Knight had been privately prosecuted but found not guilty, due to the inadmissibility of Duwayne Brooks’ identification of them as the killers. Fifteen years on, the Lord Justice endorsed the original decision of the presiding Justice Curtis, stating that to have admitted Brooks’ evidence ‘would amount to an injustice, and the injustice suffered by the Lawrence family could not be cured by adding another to the one they were already suffering’.10

The judgement emphasised the centrality of Sections 78 and 79 of the Criminal Justice Act to the decision as to whether to quash Dobson’s earlier acquittal or not. Regarding the former, The Lord Chief explained that the requirement any new evidence must be compelling ‘does not mean that the evidence must be irresistible, or that absolute proof of guilt is required. In other words, the court should not and is certainly not required to usurp the function of the jury, or, if a new trial is ordered, to indicate to the jury what the verdict should be.’11

He added that ‘the legislative structure does not suggest that availability of a realistic defence argument which may serve to undermine the reliability or probative value of the new evidence must, of itself, preclude an order quashing the acquittal.’12

The Lord Chief Justice explained how neither clothing worn by Stephen Lawrence at the time of his murder, nor that belonging to Dobson that was examined by the police, had generated sufficient evidence placing Dobson at the scene of the crime when he was tried in 1996. He highlighted that the investigation which produced this available evidence had been ‘marred by incompetence’, and that this ‘unhappy history’ raised two possibilities: firstly, whether it impaired the reliability of the evidence now available; and secondly, whether that evidence ought to have been available to the prosecution when the case first went to trial.13

He explained that the methods undertaken by the forensic scientists during the original investigation were in keeping with general practice at that time. The search for blood on assailants’ clothes therefore ‘only involved the use of a low power microscope in relation to specific areas such as seams’.14 Moreover, while tapings were taken from both the suspected assailants’ and the victim’s clothing, the police’s delay in seizing the clothing Dobson and other might have worn in the attack meant the tapings from them were deemed unlikely to still have sufficient fibres from Stephen Lawrence’s clothing to provide a definite match.

Yet the Lord Chief Justice noted: ‘Over the years greater experience and increased knowledge and expertise have produced incremental improvements in the way in which questions of this kind are examined and scientists have reconsidered the way in which they should be conducted.’15

Thus, LGC had managed to find a tiny blood stain on the collar of Dobson’s jacket and flakes of blood on the tapings taken from his coat and cardigan during the original investigation, and among debris in the bags that they were stored in. The blood stain and some of the flakes provided a complete DNA profile matching that of Stephen Lawrence, with the probability of there being an unrelated person in the UK with the same profile estimated at one in a billion. The evidence from the clothes, tapings, and bags also included a handful of acrylic fibres indistinguishable from those present on Stephen Lawrence’s jacket. Identified using technology and methods not available during the 1990s, this counted as new evidence.

QC John Roberts’s counter case was that both standard practices involved in storing evidence in the 1990s, and errors particular to the handling of items obtained by the police in this investigation, meant there were multiple occasions at which the evidence integrity could easily have been compromised. The court asked an expert witness to examine the evidence and consider the viability of Roberts’s arguments. According to the Chief Justice: ‘Her overall conclusion was that she accepted there had been a number of hypothetical opportunities for cross-contamination to have occurred, but on detailed examination the risk of such cross-contamination was so remote that it could safely be excluded.’16

The other principal issue of contention came under Section 79: specifically, the possibility of a fair trial. In his judgement, the Chief Justice noted the ‘unusually high level of media attention’ that the case had attracted.17 He attributed the scale of public interest as follows:

In part it is because every decent individual in this country (whatever his or her racial background) had come to hope that racism with such desperate consequences had been eradicated from our society. It is caused in part by the overwhelming wave of public sympathy for the parents of Stephen Lawrence and the dignified way in which they have endured the disaster that has overtaken them. And it is also caused in part because, for whatever reason, no one has been brought to justice for a killing which occurred on the streets of London.18

Commenting on the spikes in media coverage that had persisted since the failed prosecution in 1997, and the angles they had taken, the Chief Justice explained that prior to the Criminal Justice Act being passed in 2003, ‘There was no reason at all for any newspaper or television company to be circumspect in its reports and comments, or, subject only to the laws of defamation, to hold back from expressing robust views about the case, or the investigative process, or even the identity of those believed to have been involved in or responsible for the death of Stephen Lawrence.’19

Roberts argued that both negative depictions of Dobson and the other suspects in the case, and the specific claims made at times that they were guilty of killing, were likely to prejudice any future juror, at least subconsciously, in a subsequent court case. Representing the prosecution, Mark Ellison conceded the potentially prejudicial nature of the case’s coverage, but that this could be supplanted in the jury’s minds with proper judicial direction, and through the practical matter of considering the newly available evidence.

In the Chief Justice’s reading, the logical corollary of Roberts’ contention was that ‘the publicity over the years has now created an ineradicable prejudice against the [five men originally suspected of killing Stephen Lawrence] with the result that they have been immunised against the risk of prosecution. That would indeed be a remarkable result.’20 He drew upon previous judgements asserting that the evidence-focused structure of the court case, the guidance offered by judges, and jurors’ own belief in defendants’ right to a fair trial all functioned as effective counterweights to prejudicial coverage.

Based on these two conclusions about the significance of the new evidence and the possibility of a fair trial taking place, the Chief Justice acceded to Keir Starmer’s request and quashed Dobson’s original acquittal. Dobson and Norris were put on trial later that year and found guilty of Stephen Lawrence’s murder in early 2012. Dobson was given a jail term of 15 years and 2 months, and Norris 14 years and 3 months; the relative brevity of these sentences was due to the fact they were juveniles at the time.

Rehabilitating the system?

The rule change that the government advocated for based upon the murder of Stephen Lawrence ultimately enabled the eventual conviction of one of the men originally suspected of the crime. And in passing judgement in the case of R v Dobson, Chief Justice Judge vocalised many of the logics that also underpinned that rule change.

Firstly, both the Criminal Justice Act 2003 and the judgement in R v Dobson aimed to construct a community of justice, capable of incorporating most of British public opinion and elide usual ideological divides. In the Chief Justice’s view, continuing public interest in the case was a product of hostility to racism, empathy with the wronged, and outrage at a flagrant act of violence unpunished.

Secondly, they were both rooted in a belief that progress could be achieved in spite of and through addressing past injustice. Keir Starmer as Director of Public Prosecutions, and ultimately Chief Justice Judge, believed that developments in forensic science had generated evidence that changed the circumstances that had previously prevented one of the men widely suspected of killing Stephen Lawrence from being convicted for it. In doing so, they created the circumstances in which such a conviction could take place.

The Chief Justice therefore interpreted the passing of time as a boon to attaining justice, not an obstacle. In doing, so he rejected the arguments made by defence QC John Roberts, which basically held that the opposite was true: the passing of time meant the compromising of evidence, and entrenchment of public beliefs about the case and defendant that made a fair trial impossible. The defence sought, unsuccessfully, to exploit some of the ambiguities in the Criminal Justice Act that offered a check on state power vis-à-vis the liberties of the individual, and offered some guarantee that closure could be achieved in a criminal case in the event of a ‘not guilty’ as well as a ‘guilty’ verdict.

Read together, I think these documents comprise an attempt to rehabilitate the criminal justice system; to re-establish it as a solution to rather than source of injustice, and redeem British society in the process. The continuing presence of racial hatred in that society took Stephen Lawrence’s life, but the state drew upon an imagined public consensus against racism and violence to isolate and condemn the men who brandished the knives.

Institutional racism in the Metropolitan Police had hugely contributed to the original failure to convict those men, but Chief Justice Judge was careful to exonerate both forensic scientists who had examined the evidence the police provided them with, and the judicial system for not previously handing out convictions based on flawed evidence. Now advancements in forensics and the ongoing robustness of the legal system would ensure the trial not possible in the 1990s could happen now, promising a moment of catharsis, a symbolic moral victory to set against that earlier nadir in race relations in charting a trajectory of progress.

In short, the course from the Macpherson report to the quashing of Norris’s acquittal demonstrated a Whiggish logic that meant continuing to load the criminal justice system with a responsibility it could not possibly bear. To expect a system designed to identify and penalise individual agency and culpability to address wider societal and institutional forces that individual crimes are symptoms of. Forces that the criminal justice system is in many ways itself a product and perpetuator of. To create new rituals through which the state could atone for itself and the community it sought to represent and protect, by individuating and incarcerating. To evade difficult questions about the relationship between past and present, about the potential incompatibility of different notions of justice, by assuming that being tough on crime and tough on the causes of crime are not just complementary, but indistinguishable from one other.

If you’ve enjoyed this post, you can also show your appreciation by sharing it more widely, recommending the newsletter to a friend, and if you’d like, by buying me a coffee.

On the rise of the cold case, see:

Howard Atkin and Jason Roach, ‘Spot the Difference: Comparing Current and Historic Homicide Investigations in the UK’, Journal of Cold Case Reviews, Vol. 1, No. 1 (2015), pp. 5–21.

Robert C. Davis, Carl Jensen, Lorrianne Kuykendall, and Kristin Gallagher, ‘Policies and Practices in Cold Cases: An Exploratory Study’, Policing: An International Journal, Vol. 38, No. 4 (2015), pp. 610–630.

David Gaylor, Getting Away with Murder: The Re-investigation of Historic Undetected Homicide (London: UK Home Office, 2002).

Martin Innes and Alan Clarke, ‘Policing the Past: Cold Case Studies, Forensic Evidence and Retroactive Social Control’, British Journal of Sociology, Vol. 60, No. 3 (2009), pp. 543–563.

Ian Waters, ‘Policing, Modernity and Postmodernity’, Policing & Society: An International Journal of Research and Policy, Vol. 7, No. 3 (2007), pp. 257–278.

On the mediation of forensic science and the cold case, see:

Kirsty Bennett, ‘The Media as an Investigative Resource: Reflections from English Cold-Case Units’, Journal of Criminal Psychology, Vol. 10, No. 2 (2020), pp. 145–166.

Ruth Penfold-Mounce, ‘Corpses, Popular Culture and Forensic Science: Public Obsession with Death’, Mortality, Vol. 21, No. 1 (2016), pp. 19–35.

Jeremy Ridgman, ‘Duty of Care: Crime Drama and the Medical Encounter’, Critical Studies in Television: The International Journal of Television Studies, Vol. 7, No. 1 (2012), pp. 1–12.

Sir William Macpherson, The Stephen Lawrence Inquiry: Report of an Inquiry by Sir William Macpherson of Cluny (London: The Stationery Office, 1999), para 7.46.

Home Office, Justice for All (London: Stationery Office, 2002).

Criminal Justice Act 2003 (c. 44) (London: The Stationery Office), section 78.

Ibid., section 79.

Regina v Dobson [2011] EWCA Crim 1255 (18 May 2011), para. 2.

Ibid., para. 16.

Ibid., para. 20.

Ibid., para. 21.

Ibid., paras. 36, 40.

Ibid., para. 46.

Ibid, para. 47.

Ibid., para. 73.

Ibid., para. 80.

Ibid., para. 80.

Ibid., para. 80.

Ibid., para. 85.