‘This Is Going to Be Part of Soccer History’

American Samoa’s 2-1 win over Tonga in 2011 ended a lengthy losing streak and was portrayed by international media as completing a redemption arc from their 31-0 loss to Australia a decade earlier.

Please support my work by becoming a free or a paid subscriber to the newsletter. Paid subscribers are vital to me being able to continue producing and expanding this newsletter.

You can also support my work by making a one-off payment, at a price you consider affordable.

This post is part of the ‘Research and Reflections’ occasional series, consisting of pieces based on my ongoing academic research, as well as on my musings on and responses to current affairs and personal developments.

Content warning: Bereavement; Alcoholism; Transphobia and misgendering.

This is the final (long-delayed – mea culpa!) third part of a trilogy of posts on the American Samoan men’s team’s 31-0 defeat to Australia in Coffs Harbour in 2001, and the consequences of that defeat for Oceanian football and the discourse around it over the next decade. Part One reflected upon the build-up to the match, with coach Tuona Lui being forced by changes in eligibility rules to select a side of mostly uncapped teenagers; and the way the result was interpreted by both the American Samoans and in Australia, as well as internationally:

Part Two, meanwhile, examined the longer aftermath of the game from the Australian perspective. The damage results like this did to Oceanian football’s reputation, and accompanying lack of a direct qualification route from the continent, culminated in Football Federation Australia successfully applying to join the Asian Football Confederation instead in 2005:

This final post in the series completes the story by detailing how American Samoa eventually overcame the legacy of setting such an unwanted record, and escaped their position at the bottom of the FIFA rankings. In 2011, a decade after that humiliating defeat to Australia, they managed their first ever victory in international football with a 2-1 win over Tonga during the first-round group stage of qualifiers for the 2014 World Cup, under Dutch-American coach Thomas Rongen.

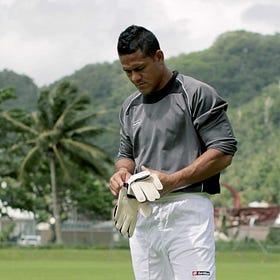

Rongen’s time with the American Samoan team was subsequently the subject of the award-winning 2014 documentary Next Goal Wins, adapted for the 2023 Hollywood feature film of the same name. However, I want to focus here on the media narrative that developed around this match even prior to the documentary’s release, as the conclusion of a redemption arc narrative. It was a narrative with a particular set of heroes, most prominently the journeyman coach Rongen, veteran goalkeeper Nicky Salapu (who had been in goal during the 31-0 defeat to Australia), and young centre back Jaiyah Saelua, a faʻafafine and trans woman who broke ground for transgender representation in the sport.1

A legacy of humiliation

Absent subsequent encounters with the likes of Australia due to the modifications to qualification to keep the continent’s weakest and strongest sides from playing each other, American Samoa nonetheless continued to suffer heavy defeats to other Oceania Football Confederation members during the 2000s, albeit not quite of the scale of that nadir in Coffs Park. Their record in subsequent tournaments over the next decade was as follows:

OFC Nations Cup qualifiers (2002): Played 4, lost 4. Scored 2, conceded 29.

OFC Nations Cup first round (2004): Played 4, lost 4. Scored 1, conceded 34.2

South Pacific Games (2007): Played 4, lost 4. Scored 1, conceded 38.3

Pacific Games (2011): Played 5, lost 5. Scored 0, conceded 26.4

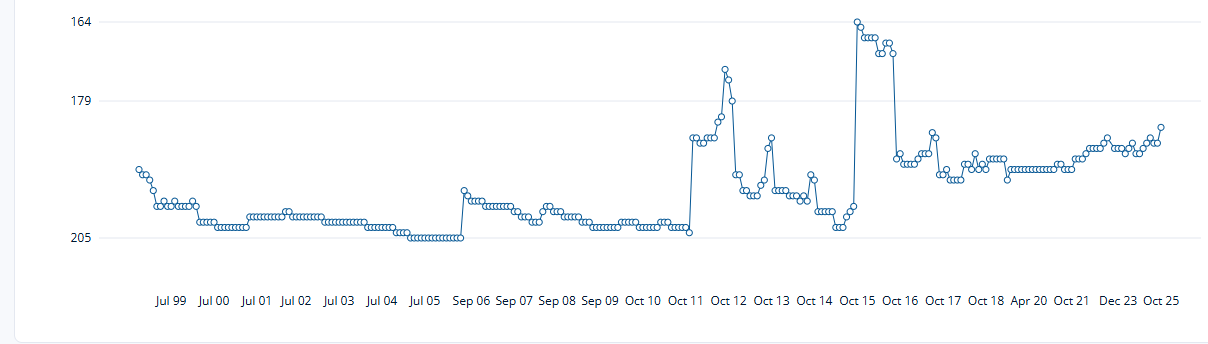

During that time, the team unsurprisingly remained close to or at the very bottom of the FIFA rankings, the worst or near-worst rated of the Federation’s 200 or so members. Football in the country was also badly affected by the 2009 Samoa earthquake and tsunami, which killed 189 people across Samoa, American Samoa, and Tonga, and also destroyed recently built football facilities in American Samoa’s capital Pago Pago.

In the decade after the 31-0 defeat, American Samoa retained a presence in the global football imaginary principally as a punchline, a byword for footballing ineptitude or insignificance. Writing detrimentally for the Financial Times about the hosts’ prospects ahead of the 2006 World Cup in Germany, Simon Kuper remarked:

The Germans have dropped to 22nd in football’s world rankings. This may seem disappointing for a country that has won three World Cups, whose football association claims to be the world’s largest sports body with 6.3m members. But again, looking on the bright side as Klinsmann always does, they still remain well ahead of American Samoa in 205th place. And looking back a generation from now, when Germany’s collapsing birthrate will have left it almost without inhabitants, 22nd will seem quite commendable.5

Later that same year, Jeff Powell, in an article for the Daily Mail that was otherwise positive about the right of smaller European national sides to play teams like England and Scotland despite the gulf in quality between them – both because ‘yesterday’s whipping boy can become tomorrow’s task master’ and ‘Football should not be the private preserve of the rich and powerful’ – nonetheless still included the aside: ‘Mercifully, England are unlikely ever to play American Samoa, against whom one Archie Thompson set an all-time high of 13 goals in Australia’s World Cup record victory of 31-0.’6

British interest in American Samoan football was briefly piqued again a year later, when Mancunian David Brand oversaw the team’s unsuccessful 2007 South Pacific Games campaign. Simon Bird profiled Brand for the Daily Mirror, again using American Samoa as a device for placing England’s travails into perspective, in language that carried heavy echoes of British imperialism in the region. He described Brand as ‘a footballing missionary’, who was bringing football to, in Brand’s own words, ‘a volcanic rock in the Pacific Ocean’. Bird noted that the coach had only forty available players to select a squad from, was personally responsible for ensuring the team’s kits were washed, and that the island had only just opened its first set of proper pitches. Brand also jokingly compared his and then England coach Steve McLaren’s lots, remarking: ‘While England will be put up in a great hotel, my lads are sleeping in bunk beds in a school classroom in 32C heat and being eaten by mosquitoes.’7

In 2008, The Guardian followed up with Brand’s predecessor – and at this point Football Federation American Samoa’s development officer – Tuona Lui about his experience of being in charge for the Australia game seven years earlier. While Lui and his peers in American Samoan football had been publicly upbeat in the aftermath of that defeat, on this occasion he was more open about what he felt was Australia purposefully humiliating his makeshift team: ‘I couldn’t see any reason why they wanted to score that many goals.’ He also spoke about his discomfort with the wider scrutiny brought about by the result:

There was a lot of attention after the game. The media came to our hotel, we were all interviewed. I didn’t enjoy that at all. We just wanted to get on with our job. People still talk to me about that game now but the past is the past. We need to move forward.8

Victory at long last

Under the newly amended structure of qualifying for the 2014 World Cup, the four lowest ranked sides in the OFC would play each other in a single round-robin tournament held in Samoa in November 2011. These teams were Samoa themselves, Tonga, Cook Islands, and American Samoa. The side that topped this group would then qualify for the eight-team OFC Nations Cup. The four teams that qualified for the semi-finals from the group stage of the Nations Cup would, separate from those matches and the final, play each other home and away in another round-robin group. The winner of this third qualifying stage would reach another dreaded inter-confederation playoff, this time against the fourth-placed from the Confederation of North, Central America and Caribbean Association Football qualification tournament.

All of this was a distant prospect for the American Samoan team as they embarked to neighbouring Samoa. They did so under the tutelage of recently appointed coach Thomas Rongen. Born in Amsterdam, Rongen played for local club Amsterdamsche FC during the 1970s, before moving to the US at the end of the decade. While continuing to play football, he transitioned to a career in coaching at high school and then college level (with a brief stint in the short-lived American Soccer League in between), before then taking the helm at several clubs in the newly established Major League Soccer from the mid-1990s. He spent most of the 2000s coaching the US men’s Under-20s across two spells, but when the side failed to qualify for 2011 Under-20 World Cup, the United States Soccer Federation decided not to renew his contract. Instead, Rongen accepted a short-term stint in one of the US’s overseas territories, training the American Samoa team for three weeks ahead of the qualifying round.

They kicked off the OFC World Cup qualifying process with their opening match against Tonga at the National Soccer Stadium in Apia at 3:00pm on Tuesday, 22 November, in front of just 150 people (the crowd would quadruple in size for host Samoa’s match with the Cook Islands that evening). American Samoa took the lead just before half-time when New Zealand-based striker Ramin Ott, who had featured for the national side since 2004, hit a shot from distance that Tongan goalkeeper Kaneti Felela misjudged and spilt into the net. In the 74th minute, teenage forward Shalom Luani – who had only made his full debut in that summer’s Pacific Cup, and would subsequently switch codes to play American Football at college and then National Football League level – ran onto a pass and lobbed the onrushing Felela for a second. Tonga’s Unaloto Feao headed past Nicky Salapu for a late goal back, but American Samoa clung on for their first ever win in a FIFA-sanctioned international.

Given American Samoa’s long-held status as the world’s worst team, the result captured international attention. Reporting on the game made much of the length of the team’s barren run, and the contrast between the drama of the moment and the lowliness of the setting for it. An Associated Press piece carried by the Canadian Press opened in exemplary fashion:

American Samoa’s players raised their arms and fell to the ground, as if they had won a major championship.

It was only a 2-1 victory over Tonga in the start of Oceania World Cup qualifying Tuesday night, but for soccer’s worst national team it was a triumph like no other.9

Writing for The Times, Sophie Tedmanson struck a similar note, remarking: ‘The Pacific island nation celebrated as if they had won the World Cup, even though they had only beaten the neighbouring island of Tonga by one goal in the start of the Oceania regional qualifying rounds.’10 These reports routinely mentioned by way of context the duration of American Samoa’s wait for a victory after 30 straight defeats, their lengthy status as FIFA’s bottom-ranked side, and the ignominious 31-0 defeat to Australia a decade earlier. The emotional significance of the match was encapsulated by a quote from Rongen, carried by a number of reports, that ‘This is going to be part of soccer history, like the 31-0 against Australia was part of history’.11

That evening, Samoa beat Cook Islands 3-2 with an injury-time goal. Two days later, American Samoa would make it two consecutive matches without defeat with a 1-1 draw with Cook Islands, Shalom Luani scoring again in the first half, before their opponents levelled in the second with an own goal by Tala Luvu. Samoa’s ensuing 1-1 draw with Tonga, the hosts conceding a late equaliser this time, left the two neighbours level on points and goal difference at the top of the group, albeit with Samoa ahead on goals scored.

On 26 November, after Tonga had beat Cook Islands 2-1, Samoa and American Samoa played the group decider in front of 800 fans. A tight game was ultimately decided by a Silao Malo goal for Samoa in the 89th minute, taking the hosts through to the OFC Nations Cup and the next round of qualifying, at American Samoa’s expense. Despite that disappointment, their performances in Apia earned them a great deal of credit, including OFC General Secretary Tai Nicholas nominating them the following month for a FIFA Fair Play Award, on account of the spirit in which they always played the game despite their long prior losing record and unenviable reputation.12

Thomas Rongen and a European perspective on American Samoa

Among the American Samoan squad and coaching team, international news media picked three people in particular to elevate above the rest of this cast of characters as encapsulating the moment. The first of these was Rongen, whose own journeyman background, quotability, and status as European-American insider/outsider figure within the American Samoan setup made him an ideal interlocutor for their campaign from the perspective of the Global North’s press. Much was made of the fact he apparently had no idea where the country was when the FFAS approached the USSF about his services. He was cast in the vein of a white saviour figure, the coach whose very Europeanness and accompanying professionalism was taken as inherently contrasting with but capable of transforming the ineptitude and amateurism of his new charges.

In a piece for the Observer on the team and the documentary then in production about them, for example, Rob Bagchi remarked: ‘Within a week of the arrival of the ‘Palagi’ – the Samoan word for white off-islanders which translates literally as ‘cloud-burster’ – the improvements in organisation and discipline were extraordinary.’13 Rongen himself had previously been quoted as stating ‘When I got here, I had never seen a lower standard of international football.’14 He subsequently explained how, while ‘steeped in the Dutch football tradition’ and committed to a ‘technical brand of football’, he had adopted more cautious tactics with American Samoa to address the glut of goals they had been conceding. ‘It’s easier to teach inexperienced players how to defend than to attack but we’ve made great strides in organisation and communication.’ Yet he also insisted that the psychological transition the players had had to make was the greater challenge:

Even in training games they lacked confidence. We’ve had meditation, yoga sessions, trying to instil in them that they have to live in the now not the past, a process of continuous positive reinforcement. There’s a traditional hierarchy, too, which is a delicate matter. I have tried to break through a cultural barrier so they can solve problems without looking to me, their elder on the sidelines and asking: ‘Coach, what do we have to do?’15

Yet Rongen was also vocal in his admiration for the players’ commitment, which he saw as capturing something of the sport at its purest:

They’re not getting anything to be here and some are spending time away from their jobs and are losing money because of that.

It’s amateur football at its best. The game at the highest level can be very cynical, but this is just about 23 guys making sacrifices.16

He explicitly drew out the romantic identification between small state nation sides and the European grassroots game, which had underpinned many of the more sympathetic earlier media accounts of American Samoa’s football team, noting: ‘This reminds me of my roots in the Netherlands, when you played for love, not money. You don’t see much of that in football any more, so it’s very refreshing.’17

Moreover, Rongen portrayed himself as someone with an inclination towards the qualities American Samoa possessed as a type of place:

I live in Florida and own some property in the Bahamas, so I’m an island kind of guy. I looked at a map and said to my wife, ‘Hey, it’s an island. Do you want to do it?’ She said, ‘Let’s go’. So we headed down.18

What he found there, he stressed, was something both distinct from his own heritage and nature and yet therefore all the more transformative and improving of him too. This was especially the case given his own personal traumas – his stepdaughter Nicole having been killed in a car crash aged 19 seven years earlier – and the strenuous and disenchanted nature of Western life (and of coaching as a career within that):

Back home in DC I’d blast to work past the Pentagon, thinking I’d got to lead my team into battle because if I didn’t I would lose my job. Here there is a methodical, pure, slow way and I have slowed down and thought about my daughter a lot more than I have recently. It’s reconnected me with the things that are important in life. I am an atheist but the religion and culture here are so strong it’s like a spiritual experience. I don’t believe in God. But there is a connection I feel, something special.19

Nicky Salapu and the passage from trauma to vindication

Of the players themselves, the one who most naturally embodied the sort of redemption arc media outlets presented was keeper Nicky Salapu, because it was he who had conceded those 31 goals against Australia. Rongen himself was quoted as saying of Salapu after the 2-1 win over Tonga:

This guy’s got major demons going on. He’s totally driven by the 31-0 score and erasing it for himself and his family. When he mentions American Samoa, people say, ‘You’re the guy that gave up 31 goals.’ There are incredible scars.20

The Irish Times made light-hearted reference to this in naming Salapu as ‘Star of the Week’ after his exploits, concluding:

Still, Salapu has an even bigger ambition: ‘For me personally, after that (31-0) experience, I really want to go back and play Australia one more time before I die.’ Nicky? Don’t do it.21

This effort to turn American Samoa’s win into a feel-good narrative about the underdog finally having it day, with fluffy human interest stories attached, meant partly eliding just how genuinely damaging an experience the defeat to Australia had been for Salapu. Rob Bagchi noted more candidly in his piece for The Observer:

He admits he found it difficult to cope with the shame and turned to drink for a while, but a friend’s gift of a PlayStation allowed him to undergo a unique form of self-diagnosed therapy. Sadly, American Samoa, the bottom-ranked team since 1998, are not one of the teams available on the FIFA series of games. He loaded a match between Samoa and Australia instead, left one controller idle and guided Samoa to a 50-0 victory which, he says, helped him get the real defeat out of his system.22

Salapu himself publicly remarked after the Tonga game ‘I feel like a champ right now. Finally I’m going to put the past behind me.’23 A few days later he was given a more extensive profile and interview by the New Zealand Herald, which again framed Salapu’s career as a perennial loser-turned-hero narrative, one of overcoming adversity through perseverance:

Imagine the worst day of your working life. Then imagine the whole world knowing about it and being reminded about it constantly over a decade. Nicky Salapu was the goalkeeper for American Samoa when they were beaten 31-0 by Australia in 2001, which remains the record defeat in international competition.

Salapu didn’t quit. He ignored the barbs and the constant jibes and kept on playing. In one of the feel good sporting stories of the year – move over Stephen Donald – Salapu has found redemption.24

Salapu himself reiterated the sense of shame he had carried with him, not least being repeatedly reminded about the Australia game whenever people learned that he played football for American Samoa, which he described as ‘frustrating and embarrassing’. He felt their performances in this qualifying round had established a clear distinction between the team thrashed that day and the American Samoan team now: ‘It makes me excited because the younger generation is going to look up and say I want to be a part of that team.’25

The story also dealt with a relatively underreported aspect of the American Samoan football side: that these were not players who had spent their lives on relative seclusion on the island, but often part of a substantial diaspora, based especially frequently in the US, yet retaining connections with and regularly returning to their country of origin. In Salapu’s case, the story of his international career and the early disappointment he strove to overcome was also one of emigration and repeated return. He had moved some eight years previously to Seattle, where he still played football several times a week ‘mainly for fun and to maintain my fitness’, yet continued to travel back to play for American Samoa’s national team when called upon. This time he would be able to go back to the US without bearing the burden of repeated defeats: ‘I’ll bury that over here and go back to Seattle and everything will be perfect.’26

Jaiyah Saelua as faʻafafine star

The other American Samoa player to capture media attention was some eight years Salapu’s junior and had in fact been coached by him as a youth. Jaiyah Saelua, previously named Johnny, is faʻafafine: though born male-presenting, she had from childhood identified as and was raised as a girl. Her presence in the side was treated as something of an additional curiosity to go with the unlikelihood of American Samoa’s long-awaited victory, being described in various outlets as the first appearance of a transgender athlete in World Cup football.27 Several articles carried Rongen’s own quote about the player: ‘I’ve really got a female starting at centre back. Can you imagine that in England or Spain?’28 Again, the coach served here as interlocutor to the exoticism of American Samoan culture and football, to emphasise its distinctness from its European counterparts.

Mostly, this interest in Saelua was fairly shallow, rather than treating her as especially ground-breaking or more widely significant. Sophie Tedmanson, writing for The Times, referred to the player as Johnny ‘Jayieh’ Saelua, explaining: ‘He is considered to be a fa’afafine, a biological male with feminine traits, widely recognised in Polynesian culture as a third sex.’29 Kathy Marks remarked in the Independent: ‘Among the players savouring the unaccustomed taste of success was Johnny Saelua, a man who considers himself a woman, or rather a fa’afafine - a ‘third sex’ common in Polynesia.’30 This misgendering of Saelua, and accompanying location of her gender identity specifically within its local context, as well as at odds with biological reality, was a common undercurrent in this reporting.

The Sun, meanwhile, remarked of Saelua’s appearance: ‘An amazing story like a scene from cult movie classic The Crying Game is emerging from the farthest reaches of the international footballing world.’ Yet while also calling the player ‘a transgender’ and stating that in Western culture she would be called ‘a ladyboy’, the piece did also consistently refer to Saelua as ‘she’. It also pointed out that ‘Far from being a delicate winger, Jayieh ‘Johnny’ Saelua plays centre half’, and seemed to take pleasure in the possibility that her appearance in Apia would discomfort then FIFA President Sepp Blatter, ‘who has reactionary views on almost everything, and especially women in football’.31

Saelua herself was also widely quoted as asserting after the match: ‘The team accept me and we have that mutual respect. Which is great. It’s all part of the culture.’32 More in-depth pieces on the player and team gave her further scope to explain her position as a fa’afafine in American Samoa and in its football team, stressing the inclusivity of both. A piece by Michael Cockerill for Australia’s The Age quoted her as follows:

When I go out into the game, I put aside the fact that I’m a girl, or a boy, or whatever, and just concentrate on representing my country…

In my country, we’re very open-minded about transgender, we can do whatever we want, play whatever sport we want. There is no discrimination. I’ve played American football, but now I’m playing soccer, because people told me I was good at it. And now we’re making history. I’m so proud of the team, it’s very exciting.33

James Montague’s lengthier profile of Saelua for the New York Times featured a more extensive explanation of the fa’afafine’s status in the country, including interviewing Alex Su’a, head of the Samoa Fa’afafine Society, about their important role in Samoan society, separate to those of men and women, such as caring for elders. Saelua herself told Montague: ‘I just go out and play soccer as a soccer player…Not as transgender, not as a boy and not as a girl. Just as a soccer player.’ Yet she also implicitly acknowledged an element of jeopardy, that it was not a given that she be accepted, and that she appreciated that her teammates ‘don’t make me feel different because I am the way I am’. She was also cognisant that as a fa’afafine, she could serve as a possible role model beyond her own country:

I hope I can inspire people. Not only transgender but anybody who feels different in their society or community. If there’s something you love to do, go out and don’t let anybody stop you from chasing after your dreams.34

This ambiguity as to whether her gender identity did not matter, or in fact gave her a particular part to play, also surfaced in Rob Bagchi’s Observer article, which quoted her as saying:

I put aside whether I’m a girl or a boy and just concentrate on playing. I think I add a third dimension to the team, collect my energies and keep the team together, that’s my responsibility as the fa’afafine.35

The reported responses of others in the American Samoan camp to Saelua also illustrated this ambiguity and the possible fragility of her acceptance. Bagchi noted that her teammates called the player ‘sister’.36 Yet Salapu’s comments to Montague about his younger teammate suggested a slightly more live-and-let-live attitude, adopted self-consciously in response to wider prejudice:

He’s like a brother to us and he’s like a sister to us. In the Samoan way, lots of people are making jokes about [the fa’afafine]. It’s difficult for their situation. I let people do whatever they want. It’s their life. He’s part of our family right now.37

Meanwhile, the FFAS’s general secretary Tavita Taumua couched Saelua’s strengths as a player in masculinist terms, telling the Associated Press: ‘He’s been a member of the team for a number of years. Yes, he’s fa’afafine but he’s a man and he plays as a man.’38

From the vantage point of nearly a decade-and-a-half later, what is quite striking about the international coverage of Saelua at the time is that, while littered with ignorance and stereotypes, it lacked the ideological charge of present-day discourse around transgender sporting participation. Perhaps that owed much to the Samoan specificity of her gender identity, perhaps even more so to her playing in men’s rather than women’s football – that Taumua’s perception that ‘he’s fa’afafine but he’s a man and he plays as a man’ held wider purchase. Nonetheless, it is also a reminder of how much explicitly ideological work, beyond simply everyday prejudices, have gone into making trans-exclusionary positions normative in sports media and administration in that time, and that this was neither inevitable, nor now irreversible.

If you’ve enjoyed this post, please consider supporting my work by becoming a free or a paid subscriber to the newsletter. Paid subscribers are vital to me being able to continue producing and expanding this newsletter.

You can also support my work by making a one-off payment, at a price you consider affordable.

Otherwise, please show your appreciation by sharing this post more widely, and referring the newsletter to friends.

You might also enjoy these posts from the Academic Bubble archive:

Next Goal Wins

Using the familiar tropes of the feelgood sports film, Next Goal Wins gently challenges Western social priorities, and affirms gender nonconformity, from a Pasifika perspective.

Next Goal Wins (2014)

This documentary follows American Samoa’s heroic efforts to qualify for the 2014 World Cup, and treats this subject in ways somewhat distinctive from Taika Waititi’s feature film of the same name.

‘We Don’t Need to Play These Games’

Australia’s 31-0 victory over American Samoa in 2001 caused the victor as much embarrassment as the loser, and provoked both scorn and amusement over in Britain.

Faʻafafine are a third gender present in Samoan society,

Also functioned as qualifiers for the 2006 World Cup.

Also functioned as qualifiers for the 2010 World Cup.

This competition had initially been intended to double up as qualifiers for the 2014 World Cup, until FIFA revised qualification rules for that tournament.

Simon Kuper, ‘World Cup Shaping up Like ‘Star Wars’ without Darth Vader’, Financial Times (18 Mar. 2006).

Jeff Powell, ‘Take Turkeys to Hull and Back!’, Daily Mail (4 Sep. 2006).

Simon Bird, ‘I Have a Tougher Job than McClaren...I Even Wash the Kit’, Daily Mirror (8 Sep. 2007).

‘Australia Win World Cup Qualifier 31-0’, The Guardian (12 Apr. 2008).

Associated Press, ‘The Waters Part in Pacific: After 30 Losses, American Samoa Wins a Soccer Game’, Canadian Press (23 Nov. 2011).

Sophie Tedmanson, ‘American Samoa Win Their First Game after 17 Years’, The Times (24 Nov. 2011).

Quoted in Associated Press, ‘The Waters Part in Pacific’.

‘American Samoa Nominated for FIFA Fair Play Award’, Associated Press Online (9 Dec. 2011).

Rob Bagchi, ‘Wonder of the Island Winners’, The Observer (27 Nov. 2011).

Quoted in James Montague, ‘For American Samoa, a Win Ignites a World Cup Dream’, New York Times (24 Nov. 2011).

Quoted in Bagchi, ‘Wonder of the Island Winners’.

Quoted in ‘American Samoa, One of Soccer’s Worst Teams, Scores First Ever Win’, CNN.com (24 Nov. 2011).

Quoted in Michael Cockerill, ‘American Samoa Plays without Prejudice, for Love of the Game’, The Age (26 Nov. 2011).

Quoted in ‘American Samoa, One of Soccer’s Worst Teams, Scores First Ever Win’.

Quoted in Bagchi, ‘Wonder of the Island Winners’.

Quoted in Montague, ‘For American Samoa, a Win Ignites a World Cup Dream’.

‘All in the Game’, The Irish Times (28 Nov. 2011).

Bagchi, ‘Wonder of the Island Winners’.

Quoted in Montague, ‘For American Samoa, a Win Ignites a World Cup Dream’

‘Win Exorcises Ghosts of 31-0’, New Zealand Herald (27 Nov. 2011). Stephen Donald, whom the article compared Salapu favourably to, was the previously much maligned New Zealand rugby union international who, after an unexpected call-up back to the national team, had kicked the winning penalty in that year’s World Cup final.

Quoted in ‘Win Exorcises Ghosts of 31-0’.

Ibid.

This oft-repeated claim, assuming it was referring to qualifying for the 2011 World Cup, overlooked the fact that Saelua had in fact played for the national side in qualifying for the 2006 World Cup as a 15-year-old.

Quoted in, for example, Montague, ‘For American Samoa, a Win Ignites a World Cup Dream’; Michael Cockerill, ‘American Samoa Break Record Losing Streak’, Sydney Morning Herald (25 Nov. 2011); Sophie Tedmanson, ‘17 Years on, International Football’s Worst Run Ends amid the Coconut Palms’, The Times (25 Nov. 2011); ‘Woman of the Match’, The Sun (26 Nov. 2011).

Tedmanson, ‘17 Years on, International Football’s Worst Run Ends’.

Kathy Marks, ‘Woeful to Wonderful: World’s Worst Football Team Win at Last’, Independent (25 Nov. 2011).

‘Woman of the Match’.

Quoted for example in Montague, ‘For American Samoa, a Win Ignites a World Cup Dream’; Tedmanson, ‘17 Years on, International Football’s Worst Run Ends’; ‘Woman of the Match’.

Michael Cockerill, ‘American Samoa Plays without Prejudice, for Love of the Game’, The Age (26 Nov. 2011).

James Montague, ‘A First in Cup Qualifying For a Player and a Team’, New York Times (26 Nov. 2011).

Quoted in Bagchi, ‘Wonder of the Island Winners’.

Bagchi, ‘Wonder of the Island Winners’.

Quoted in Montague, ‘A First in Cup Qualifying For a Player and a Team’.

Quoted in ‘Glory Days for Soccer in Tiny American Samoa’, Associated Press (25 Nov. 2011).