Provos (1997)

Peter Taylor’s documentary miniseries on the history of the Provisional IRA provided space for the Republican narrative of the Troubles to be relayed – albeit not without criticism or pushback.

Please support my work by becoming a free or a paid subscriber to the newsletter. Paid subscribers can access my full archive of posts at any time, and are vital to me being able to continue producing and expanding this newsletter.

This post is part of the ‘Rewound’ series of analyses of objects or episodes from cultural and political history.

Content warnings: Death; Murder; Anti-Catholic discrimination; Bereavement.

‘The Troubles’ were a three-decade long civil conflict over the future status of Northern Ireland, and whether it would remain part of the United Kingdom or form part of a united Ireland, contested between the Republican Provisional Irish Republican Army, the Loyalist paramilitary groups the Ulster Volunteer Force and the Ulster Defence Association, and British security forces.

Its legacy has remained influential and been mobilised within Northern Ireland and beyond since around the point the conflict ended in the late 1990s, in aspects of administration, in the partial and overlapping (rather than cohesive) transitional justice process, and in mediated representations of the conflict.

As the 1990s progressed, television provided a more nuanced portrayal of the Troubles and its combatants, at the point when the conflict was coming to a close1. It was in this context that Peter Taylor’s Provos: The IRA and Sinn Fein was made and broadcast on BBC in late 1997. Yet this miniseries on the Republican movement, the first in a trilogy he made about the Troubles for the UK’s public broadcaster, was also the latest entry in the veteran journalist’s long career of covering political violence in Northern Ireland.

I therefore wanted to use this post to examine Provos, as an encapsulation of Taylor’s journalistic approach to the Troubles, and as an example of how a certain liberal framework of recalling and representing the conflict functioned, at the point when it no longer seemed intractable. I also wanted to explore how Taylor’s, and the BBC’s, approach to documentary-making incorporated the Republican counternarrative of those events.

Peter Taylor and the Troubles

Born and raised in Scarborough, Peter Taylor joined ITV’s current affairs programme This Week in 1967. In the wake of Bloody Sunday, the 1972 massacre of 14 unarmed Catholic civil rights protestors by British soldiers in Derry, he gained particular prominence for his coverage of the Troubles in Northern Ireland. In 1980, Taylor moved to the BBC and its investigative journalism programme, Panorama, for whom he continued to cover the Northern Ireland conflict, as well as writing a number of books on the topic.2

After the Troubles formally ceased with the signing of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, Taylor wrote and presented on political violence, security and espionage affairs more generally, including the rise of Al-Qaeda, and the intelligence that paved the way for Britain’s participation in the 2003 invasion of Iraq. He also perennially revisited the conflict in Northern Ireland and its legacy, with programmes such as Who Won the War? in 2014, and Peter Taylor: My Journey through the Troubles in 2019.

Responding to questions from BBC News Online users in 2000, Taylor outlined his stance on covering the Troubles and the British state’s response to it. He noted that he was regularly questioned as to why he made programmes so critical of the security forces, given the extent of the violent threat posed by terrorist organisations like the IRA. He explained:

But I think that if our security forces, or our police officers or our politicians do break the law then they should be brought to justice. A sign of the health of any liberal democracy such as ours is the ability and freedom of the media to investigate these sorts of areas. If we didn’t the democracy to which we all belong would be the weaker for it.

Being interviewed for BBC News 14 years later, Taylor also reflected on the challenges of interviewing terrorists, without simply providing them with the ‘so called oxygen of publicity’. He said that there was a balance to be struck between questioning interviewees robustly on their actions, while simultaneously retaining sufficient rapport with them to ensure continued access. The journalist’s honesty and integrity was crucial in this context, and he prized his reputation in this regard:

Trust is the key and it takes years to build it up. In the end you are judged by what you say you will do and what you actually do. There has to be a correlation between the two…There was/is a general recognition that I have a job to do and that job crucially involves being fair. When I’m in Northern Ireland, it means a lot when from time to time I’m stopped by people from both sides who say “thank you for being fair”. It’s quite a humbling experience.

Taylor’s Troubles trilogy

During the mid-to-late 1990s, Taylor began making a trilogy of miniseries for the BBC on the history of the Troubles. At this point in time, the peace process that would eventually culminate in the 1998 Good Friday Agreement and the formal cessation of the Troubles was well underway.

Each miniseries examined the Troubles with a focus on one of the sides involved in the conflict. The first, Provos, was screened on BBC One in September 1997. The second, Loyalists, which considered the role of both Loyalist paramilitaries and hard-line Unionist politicians in the Troubles, was shown on BBC Two in February 1999. Finally, Brits, which explored the perspective and conduct of the security forces, was screened in May 2000.

In a feature for the BBC News site to mark the launch of Brits, Taylor wrote:

The trilogy of the Troubles – Provos, Loyalists and now Brits – has been a massive undertaking. We didn’t set out to make a conventional history of the Troubles but wanted to explore, in the political context of the time, the actions and psyche of those at the sharp end of the conflict – the Republicans, Loyalists and Brits who did the killing and the dying.

In the aforementioned online question and answer forum for BBC Online, Taylor was asked whether he had received any threatening pushback from any of the sides for making these programmes, and replied that he had not. He noted that his team had relied on a degree of assistance from Republicans to make Provos, and that they generally saw it as ‘a pretty fair report on the history of their movement’.

Taylor also rejected the implication that the trilogy risked stirring up tensions again and jeopardising the peace process, arguing that it was rather a testament to its importance:

Memories are short unless you happen to have been a member of a family who has lost loved ones. I think it’s a very timely reminder, in particular at this critical point historically, to people of where we have all come from and why we cannot go back to it. I think that is the single most important purpose of the trilogy.

Provos: The IRA and Sinn Fein

Provos was comprised of four episodes. The first, ‘Born Again’, centred on the establishment of the Provisional IRA. It set this event within the context of the legacy of partition in 1922, and of Catholics’ experiences of state-led discrimination and then of escalating violence from their Protestant neighbours as the 1960s drew to a close.

Hopes that the recently deployed British Army might prove a more honest broker than the Royal Ulster Constabulary were also swiftly disappointed. With the existing IRA effectively a spent force militarily, the Provisionals broke away, committed to renewed armed struggle. It began accumulating arms and targeting military personnel, along with bombing commercial districts, ostensibly with the intention of only causing damage to buildings, but with frequent loss of civilian life as well.

The second episode, ‘Second Front’, concentrated on the period between the early 1970s and early 1980s. During this period, the IRA took its bombing campaign to the British mainland, proposals for a power-sharing regime foundered on Unionist recalcitrance and direct rule from Westminster was introduced, internment was introduced and then discontinued, and Republican prisoners responded to the removal of their special status with escalating protests, culminating in the 1981 hunger strike in which ten men starved to death.

The documentary presented this as a period in which Republicans were demoralised by rising numbers of arrests and the failure of negotiations with the British government, but then reinvigorated by the leadership of Gerry Adams, and the launch of a political strategy involving electoral politics and the building of a broader coalition of support.

Episode three, ‘Secret War’, examined the attrition of the 1980s. The British government deployed an effective but controversial counterinsurgency strategy, involving firstly the recruitment of ‘supergrasses’ within the IRA to inform on other paramilitaries, and then the usage of British Army special forces, the SAS, to ambush and often kill IRA members.

The episode covered the FBI’s success in shutting down the supply line of arms from America to Northern Ireland too, but also the IRA’s acquisition of large quantities of advanced weaponry from Libya. The outcome of this manoeuvring on both sides was an effective military stalemate. At the same time, Adams’ political strategy was both bearing fruit electorally, and becoming increasingly hegemonic within Sinn Fein.

The final episode, ‘Endgame’, brought the series up to the then-present day. It was the most high politics-focused of the four episodes, concentrating on the developing peace process as negotiated between existing Republican leadership, the more mainstream Nationalist Social and Democratic Labour Party, the Irish government, and the British government (as well as the belated involvement of Bill Clinton and his administration in the US).

‘Endgame’ presented a Republican leadership determined to end the war, but also needing to bring the broader, far less convinced wider membership with it, calling an indefinite ceasefire in 1994. It also covered the positive moves made in this direction by Albert Reynolds’ government in Ireland and John Major’s in the UK, including the 1993 Anglo-Irish agreement.

Disagreement over decommissioning weapons and the increasingly weak Major government’s reliance on Unionist support in Parliament threatened to derail the peace process, resulting in the IRA halting the ceasefire in 1996. However, the series concluded on a more positive note, with the election of Tony Blair as prime minister in 1997, and the IRA’s resumption of its ceasefire.

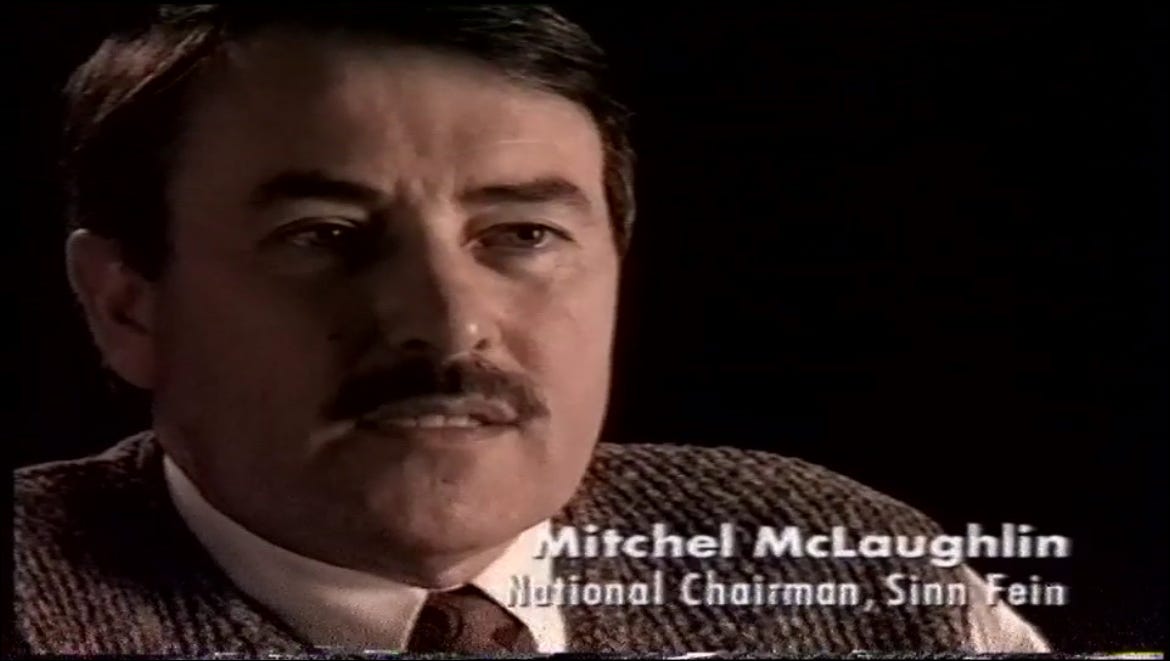

Republicans speaking for themselves

Provos drew upon historical footage from the BBC, including from programmes made by Taylor more recently, combined with that from various regional independent stations, as well as private video recordings of IRA events, and security footage of certain incidents. This was interspersed with interviews with both key Republican personnel – save for Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness, who both declined to take part on this occasion – and former government ministers and security personnel. It also made use of still photos, and previously secret documents from both the Republican and government sides. All of this was knitted together by Taylor’s narration.

Former IRA men interviewed for the programme tended to present paramilitary activity in ways that minimised the level of agency they had individually and collectively had. Unsurprisingly, they often evaded discussing their own participation in violent IRA actions in specific detail, especially where it carried risk of self-incrimination. This was most evident in ‘Secret War’, when interviewees expressed a sense of betrayal over allegations made against them by former comrades turned informers, while skirting around the substance of those declamations.

Republican interviewees framed the IRA’s use of violence more generally in ways that presented it as an inevitable result of circumstances. They stressed the extent to which they felt bound to participate in the struggle by weight of their heritage, or anti-Catholic discrimination, or provocation by the British.

When accounting for direct killings by the IRA, they would usually emphasise that the victims were agents of the British state, although occasionally there were moments of reflection – usually prompted by Taylor – on the horror this involved. One such example was in ‘Born Again’, when former Belfast Brigade officer Brendan Hughes discussed with a hint of remorse the 1973 abduction and killing of teenage soldier Gary Barlow in the city, an incident that he said ‘certainly had an effect on me’.

As for civilian deaths in bombings, Republican interviewees tended to blame these on state officials, ffor having either incompetently or deliberately not acted on warnings, as well as for having provoked the IRA in the first place. It was at points like this that Taylor’s interview style became more directly confrontational and contradicting, such as when he spoke to former IRA chief of staff Seán Mac Stíofáin about ‘Bloody Friday’. On 21 July 1972, following the breakdown of talks with the British government, the IRA exploded 20 bombs in Belfast in quick succession, killing nine people.

MAC STÍOFÁIN: The blame was with the people who deliberately had not given the warnings to the public.

TAYLOR: The blame rested with those people – your people, the IRA – who planted the bombs.

MAC STÍOFÁIN: Ah no, I don’t agree.

TAYLOR: Don’t plant the bombs, people don’t die.

MAC STÍOFÁIN: Ah well, but if the British government has persisted in its policies to the North of Ireland, you’re going to get resistance.

Taylor, however, also adopted similar tactics at times with representatives of the British side, as when interviewing police and prison officials about the brutalisation of Republican prisoners in ‘Second Front’, or querying with John Major in ‘Endgame’ why he had insisted on raising the issue of decommissioning during the peace talks, when it was so clearly an obstacle for the IRA leadership.

Occasional interviews with the bereaved also added emotional weight to what might have been otherwise matter-of-fact listing of incidents and their death tolls. One such instance came in ‘Endgame’, when Alan McBride spoke about the death of his wife Sharon McBride in the IRA’s 1993 Shankill Road bombing in Belfast. The same approach could humanise IRA men killed in the conflict, as when Amelia Arthurs spoke about the death of her son, Declan Arthurs of the East Tyrone Brigade, in an SAS ambush in 1987.

Female interviewees were generally very much in the minority in Provos, however. The series depicted women, if at all, as victims of the Troubles (with the unavoidable exception of Margaret Thatcher). Republican women, including IRA volunteers, were almost entirely absent. For example, when ‘Second Front’ covered the matter of prison protests, its focus was entirely on the participating male inmates at the Maze Prison, omitting the related events that took place at the all-women Armagh Prison.

Explaining Republican violence

Provos did not shy away from depicting the IRA’s use of violence. It used archival footage of original news coverage of the aftermaths of major bombings like Bloody Friday in 1972, or Enniskillen in 1987, as well as photographs of soldiers they had deliberately killed, to emphasise the consequences of those choices. Republican interviewees’ accounts of these events often jarred with Taylor’s far more damning commentary.

Yet at the same time, the miniseries also sought to illuminate how the Republican mindset behind this conduct developed. ‘Born Again’ focused on the severity of the sectarianism, civil rights abuses, persecution, and increasingly violence that Catholics faced in Northern Ireland prior to the Provisional IRA forming. In that regard, the resumption of paramilitary activity appears primarily as a defensive act, and the choice taken by young men to join an understandable one; although it also made it clear just how far the IRA was on the offensive by the early 1970s.

Subsequent episodes also strongly evoked, and to a degree legitimated, the sense of hope followed by disillusionment that Republicans felt when negotiations with the British government foundered on the latter’s apparent bad faith. Provos was, moreover, willing to explore (and again partly vindicate) their sense of being victims as much as perpetrators, over matters such as internment, the hunger strike, their targeting by the SAS, and Loyalist reprisals.

This was sometimes reinforced through the revelation of sources that aligned with their narrative, such as minutes from secret meetings with British officials. At other times it was through the inclusion of moderate voices on the British side at least partly sympathetic to elements of their grievances, as when former Labour Northern Ireland Secretary Merlyn Rees criticised internment in ‘Second Front’.

In many ways, Provos lived up to Taylor’s stated ambition, providing an account of the Troubles and the Republican movement’s role in them that combined rigour with even-handedness. It provided space for the Republican interpretation of those events to be included, albeit not unchallenged.

If, as Taylor claimed, they were generally satisfied with their portrayal in Provos, it is rather testament to how the trust he had accrued on different sides throughout the Troubles served as credit to exchange for their testimonies. It also illustrates the place of the Republican mindset within the broader context of the politics of the Northern Ireland conflict in the late 1990s, whereby drastically different interpretations needed not preclude meaningful dialogue.

The counterpoint, however, is that Provos could and would not assess the deeper validity (or not) of the Republican viewpoint on the status quo in Northern Ireland. Taylor criticised what he viewed as prejudice and abuses of power, and rejected overt censorship, as anathema to a liberal democracy. He did not, as the dominant voice in Provos, question whether those ills were features rather than bugs of a liberal democracy born of an imperial state, as Britain was.

If you’ve enjoyed this post, you can show your appreciation by sharing it more widely, recommending the newsletter to a friend, and if you’d like, by buying me a coffee.

See Greg McLaughlin and Stephen Baker, The Propaganda of Peace: The Role of Culture and Media in the Northern Ireland Peace Process (Bristol and Chicago, IL: Intellect, 2010).

During this decade, Taylor wrote:

Beating the Terrorists? Interrogation at Omagh, Gough, and Castlereagh (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1980).

Stalker: The Search for Truth (London: Faber & Faber, 1984).

Families at War: Voices from the Troubles (London: BBC Books, 1989).

Fascinating. I remember these series from broadcast ...