Trolls World Tour (2020)

The depiction of tribes warring over musical tastes in Trolls World Tour serves as an allegory for how even the best intentioned ideologies turn sour without due respect for difference.

Please support my work by becoming a free or a paid subscriber to the newsletter. Paid subscribers can access my full archive of posts at any time, and are vital to me being able to continue producing and expanding this newsletter.

This post is part of the ‘Rewound’ series of analyses of objects or episodes from cultural and political history.

Spoiler alert: This analysis of the film Trolls World Tour and its themes reveals plot details for the purpose of enhancing that analysis.

A couple of weeks back, I took my daughter and niece to the cinema to watch Trolls Band Together: the third instalment in DreamWorks’s series of digitally animated jukebox musicals about small, colourful, singing trolls. I did not think that much of it, aside for some arresting visual experimentation. That’s fine, I’m not the target audience, save to purchase tickets for and accompany my daughter and niece. But I do quite like the first two Trolls films, especially the second one: 2020’s Trolls World Tour, which uses the theme of troll tribes arguing over musical preferences as the basis for a clever allegory about ideology, cultural difference, and tolerance and acceptance.

DreamWorks Animation and the Trolls franchise

Troll dolls were invented by Danish craftsman Thomas Dam in the 1950s, and spread around the world from the 1960s, with episodic revivals in their popularity. DreamWorks purchased the licensing rights to the Trolls in 2013, and in 2016 released the first in its series of films about them. Trolls begins by recounting the story of how its joyful eponymous heroes, led by King Peppy (voiced in this film by Jeffrey Tambor), escaped from the far larger, far more miserable Bergens, who ritually ate them annually in a vain effort to cheer themselves up. It then shifts to the present day, when some of the Trolls are captured from their village and taken back to Bergen Town. Peppy’s relentlessly cheerful and optimistic daughter Princess Poppy (Anna Kendrick), accompanied reluctantly by curmudgeonly, paranoid loner Branch (Justin Timberlake), embark upon a quest to rescue them. They succeed in their mission, and in convincing the Bergens that happiness lies within them, not in eating Trolls. In the process, Branch and Poppy become unlikely friends, and Branch – whose perennial fearfulness is revealed to have arisen from his witnessing a Bergen eat his grandma when he was a child – loses some of his inhibitions, including around singing, and is properly integrated into the Trolls community.

Trolls – along with Shrek, Despicable Me/Minions, Sing, Madagascar, and others – is one of a number of successful franchises launched by DreamWorks since the 1990s, when it established itself as a slightly more subversive rival to Disney.1 Animation scholar Sam Summers has argued that one of the defining differences between the two studios is DreamWorks’ tendency to make more sparing use of familiar songs (either in original or re-recorded form) rather than bespoke soundtracks of entirely new songs. In doing so, it uses the existing connotations of those songs to (straightforwardly or ironically) communicate something about the films’ characters or plots to the audience, as well as taking advantage of licensing agreements for financial gain.2 Summers sees the first Trolls film as in some ways the apogee of this tendency, but not a particularly well-realised one. He argues that the film subsumes the referents of its soundtrack to the requirements of its significantly removed narrative and worldbuilding, such as in the scene when Poppy sings Simon and Garfunkel’s ‘The Sounds of Silence’ to an unappreciative Branch (see below), with little by the way of clear ordering by genre or period.3

Trolls World Tour

Trolls World Tour makes far more deliberately knowing and meaningful use of musical canon and genre than its predecessor. It begins with a rave held by the luminescent, fish-like Techno Trolls being interrupted by the arrival of the hostile Queen Barb (Rachel Bloom) and her Rock Trolls, who force them to surrender and hand over their ‘string’. The setting then shifts to Troll Village, where Poppy is now Queen, having succeeded the retired Peppy (voiced by director Walt Dohrn) as leader of the Trolls, and Branch is revealed to have developed growing feelings for her. An invitation arrives from Queen Barb, inviting them to join her Rock Trolls and others in uniting their strings and bringing the Trolls together in harmony again. Peppy reluctantly reveals that theirs is but one tribe of Trolls, the Pop Trolls, and that there are five others: the Rock Trolls, Techno Trolls, Classical Trolls, Country Trolls, and Funk Trolls. He shows Poppy a scrapbook telling the tale of how all the trolls once lived together and possessed a magical lyre that gave them the gift of music, only for their inability to stand each other’s taste in music to cause each tribes to go their separate ways, taking their respective strings with them.

Against Peppy’s advice, Poppy replies to Barb, warmly accepting her invitation, and then takes the Pop tribe’s string to join her in her quest, accompanied by a sceptical Branch, and their friend Biggie (James Corden). Meanwhile, another of their friends, the four-legged troll Cooper (Ron Funches), also secretly departs Troll Village on his own to find out more about his connection to the Funk Trolls, having noticed his resemblance to the picture of them in the scrapbook. When Poppy, Branch, and Biggie arrive at the land of the Classical Trolls to find it devastated and abandoned, they realises the truth: that Barb intends to capture the other tribes and steal their strings, rather than unite them. Unbeknownst to them, Barb has also promised several bounty hunters representing other, more specific subgenres, that she will spare their music if they capture Poppy. Poppy and her friends then travel to the land of the centaur-like Country Trolls, led by Delta Dawn (Kelly Clarkson) to warn them about Barb. However, when Poppy – finding their music far too depressing – tries to educate them about pop music through a song-and-dance routine with Branch and Biggie, the Country Trolls are so outraged that they throw them in prison. They are then sprung – in the scene shown below – by the mysterious Country Troll Hickory (Sam Rockwell). He promises to take them to Vibe City to warn the Funk Trolls, but they are attacked along the way by one of Barb’s bounty hunters, Smooth Jazz Troll Chas (Jamie Dornan), only for Hickory to again save them. Biggie is outraged that Poppy has failed so spectacularly in her promise to keep them safe, and returns to Troll Village.

Poppy, Branch, and Hickory board the spaceship-like Vibe City, where they are reunited with Cooper, who it turns out is the long-lost son of Funk Trolls King Quincy (George Clinton) and Queen Essence (Mary J. Blige), and twin brother of the rapping Prince D (Anderson .Paak). When Poppy informs them of her desire not only to defeat Barb but also to reunite the Trolls as one as they had lived before, the Funk Trolls reveal that it was in fact the Pop Trolls who were culpable for the original fragmentation of the tribes, having tried to take the others’ strings. At that point the Rock Trolls attack and the Funk Trolls eject Poppy, Branch, and Hickory for their safety. Branch and Poppy quarrel over her refusal to listen to others, and they go their separate ways. Hickory is then revealed to be not a Country Troll at all, but one of two Yodel Trolls (his brother Dickory had been pretending to be his behind) hired by Barb to catch Poppy; he urges her to flee, but they are ambushed by Barb and the Rock Trolls, who capture her and take her string. Branch is also captured by two rival bands of bounty hunters, the K-Pop Trolls and Reggaeton Trolls, but convinces them both to ally with him to defeat Barb. Biggie, meanwhile, has returned to find Troll Village has also been attacked by the Rock Trolls and most of its population captured; he gathers the few remaining Trolls together to return and rescue Poppy.

At the Rock Trolls’ home of Volcano Rock City, Barb has now attached all of the strings to her electric guitar, and plans to play a concert with it that will turn turn all the captives into Rock Trolls. Neither Biggie’s nor Branch’s rescue attempts succeed, and Branch is turned into a Rock Troll. So too, it seems, is Poppy, but this turns out to be a ruse. She manages to take and destroy Barb’s guitar, and with it the strings, causing the colour and music to drain from all of the Trolls. However, the beating of Cooper’s heart, accompanied by Prince D.’s beatboxing, demonstrates that music can continue without the strings.

Poppy leads a rendition of the film’s finale song, ‘Just Sing’, and the colour returns to her and the other trolls as they join in, including eventually Barb, at the encouragement of her father, the doddering retired King Thrash (Ozzy Osborne). Branch reveals his feelings to Poppy, and she is subsequently shown to be reading a scrapbook about the Troll tribes to youngsters drawn from all of them.

The Rock Trolls, ultranationalism, and intolerance

Heavy rock, both sonically and in its associated aggressive lyrics and imagery, is a logical selection for a genre to embody the antagonists in a children’s film, especially when counterposed with the (Pop) Trolls from the first film. This apparent villainy is signified through Queen Barb’s red-and-black Mohican hairstyle and piercings, and through the songs she performs excerpts of in the film: Scorpions’ ‘Rock You Like a Hurricane’, Ozzy Osborne’s ‘Crazy Train’, and Heart’s ‘Barracuda’. Yet there is a deeper significance here: the three songs were all originally recorded between the mid-1970s and mid-1980s, embodying a particular era and sensibility in rock music, when its increasing musical segregation from other genres on American radio was followed by the establishment of a specific Billboard ‘Rock’ chart in 1981. Associated with Whiteness, masculinity, and heteronormativity, Rock’s gatekeepers and fans sharply contrasted it with genres evoking Blackness, femininity, and/or queerness – most notably Disco – and with it changes to previously established social hierarchies.4

Barb epitomises this intolerance from the outset, telling the leader of the Techno Trolls, King Trollex, that their ‘bleeps and bloops’ are ‘not music’, before describing rock as ‘real music’. She is later equally dismissive of Pop, yelling ‘Pop isn’t even real music. It’s bland! It’s repetitive! The lyrics are empty! Worst of all, it crawls into your head like an earthworm!’ She aspires to achieve unity through annihilating any deviance from her ideals of artistic quality. The film pushes the ideological undertones of this attitude to music to the forefront, making it stand in for ultranationalism and cultural genocide. Barb asserts eagerly, ‘We’re all gonna be one nation of Trolls…under rock!’, and her version of ‘Crazy Train’ (whose original lyrics referenced the psychological strains of the social and political divides of the Cold War era), also encapsulates this sentiment.

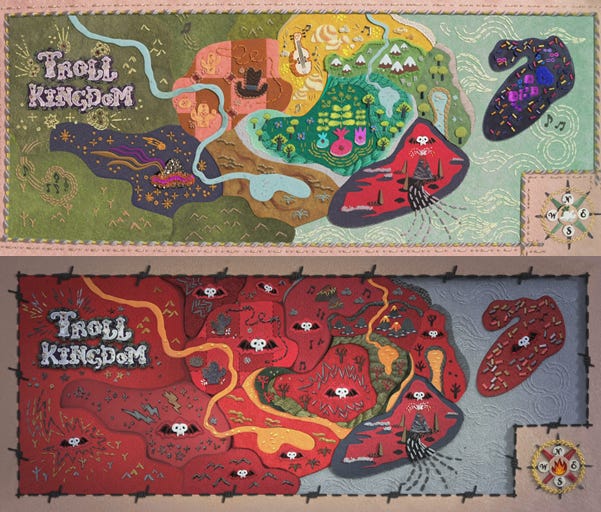

Later, she displays a map of Troll Kingdom with the territories of its separate musical tribes visually differentiated from each other, and then as it would appear once entirely dominated by the Rock Trolls (see below). Likewise, her promise of musical autonomy to the successful bounty hunters involves them having their own tiny island marked out on this map – an act of literal ghettoization. I do not think it is coincidental that three of these four sets of trolls, whose cultural autonomy is so precarious, represent genres with clearly ethnic connotations.5

Yet Barb is not depicted as a wholly unsympathetic character. She demonstrates hints throughout of vulnerabilities that help explain her behaviour and allow for her eventual reconciliation with the other Trolls at the end of the film. Her association with rock also stands in for White middle-class adolescent angst, precocity, and loneliness, which she frequently displays. That isolation is doubled by her status as a young woman in a position of authority, as she later confides to Poppy: ‘There’s all this pressure to be a great queen. And instead of real friends, you’re just surrounded by people who just tell you what you want to hear.’6

The Pop Trolls, liberal universalism, and conservative particularism

Pop music, meanwhile, is the musical embodiment of a set of norms introduced to the audience in the first Trolls films, epitomised in the first musical number: a medley of Cyndi Lauper’s ‘Girls Just Wanna Have Fun’ (re-titled ‘Trolls just wanna have fun’, and with adapted lyrics sung by Poppy about being a Queen, and by Branch about his feelings for Poppy), Chic’s ‘Good Times’, a brief party rap interlude by newest arrival Tiny Diamond, and Dee-Lite’s ‘Groove Is in the Heart’.

Later, when Poppy, Branch, and Biggie try to persuade the Country Trolls of the value of pop music, they perform a medley of The Spice Girls’ ‘Wannabe’ and Baha Men’s ‘Who Let the Dogs Out?’

This pop music canon actually comprises elements (or even entire songs) drawn from other genres, such as funk, hip-hop, and Bahamian junkanoo. This magpie-ish tendency, and its wilful blinkeredness to difference in any meaningful sense, also epitomises Poppy’s response to finding out about the existence of other Troll tribes. This is set in deliberate contradiction with Peppy’s more historically-informed communitarianism. Yet when he recounts (the Pop Trolls’ version of) how the Troll tribes came to live apart, intended as a cautionary tale, Poppy simply becomes more sympathetic to Barb’s apparent agenda: ‘She wants to reunite the strings so the Troll World can be one big party again.’ She accuses her father of ‘assuming the worst about someone you haven’t even met’ and subsequently claims ‘We’re all Trolls. Differences don’t matter’.

After learning about Barb’s true intentions, Poppy is determined to stop her, but also to still bring all of the Troll tribes together. Her naïve commitment to a project of exploration and discovery, to pursuing an un-reflected upon idea of the good, serves as metaphor for that of liberal imperialism, and its universalist underpinnings. As she tells Branch, ‘I can’t stay home when I know there’s a world full of different Trolls out there just like us.’ Branch, torn between his own conservative impulses and loyalty to Poppy, values particularism and is therefore able to respect the qualities of other cultures, and to try and understand and learn from them. This is typified by their respective responses to hearing the Country Trolls singing.

Poppy’s sense of mission, her perfectionism, is driven by her desire to prove herself as a ‘good queen’, causing her to discard all evidence contrary to her worldview. Her failure to listen is frequently commented upon by other Trolls, and ultimately prompts Branch to reaffirm his own worldview and break with her: ‘You want to be a good queen? Good queens actually listen. You know what I heard back there? Differences do matter. Like like you and me. We’re too different to get along. Just like all the other Trolls.’ Liberal universalism’s totalitarian capabilities are emphasised when Poppy ultimately meets Barb, who affirms the connections between them that Poppy had noted in her earlier letter to her, and to Poppy’s horror, the similarities in their ambitions:

BARB: You know, other than your terrible taste in music and clothing and general lifestyle, you and me are the same, Popsqueak.

POPPY [scoffing]: Uh...No, we’re not.

BARB: We’re both queens who just want to unite the world.

POPPY: You don’t want to unite the world. You want to destroy it!

BARB: Nuh-uh. No way. No. I don’t know who told you that. Music has done nothin’ but divide us. Now that I have the final string, I can make us all one nation of Trolls, under rock.

The Funk Trolls, difference, and the victory of multiculturalism

Poppy’s and Branch’s earlier encounter with the Funk Trolls serves a revelatory function within the film, both in teaching them (and the audience) the real history of the division between the Trolls, and in signalling the film’s final ideological takeaways. As a genre, funk – with its emphasis on rhythm and improvisation, and that developed at the same time as the Black Power movement – is coded as signifying Black authentic self-expression. This is further emphasised by the usage of Black voice actors, three of whom are also primarily musical artists, for the Funk Troll royal family. It is also encapsulated in the Afro-futurist trappings of Vibe City, matched by the usage of Clinton’s own song ‘Atomic Dog’ on the soundtrack when Poppy and her coterie arrive there.

This scene champions hybridity and evolution in Black music, as signified by the new musical directions Cooper and Prince D have taken compared to their parents. Cooper tells Poppy: ‘You don’t have to be just one thing. I’m Pop and Funk.’ Yet when Poppy tells the Funk Trolls of her desire to show Barb ‘that music unites all Trolls, and that we’re all the same, and that she’s one of us!’, they push respectfully back. Prince D begins to explain the true history of how the Trolls became divided and when Poppy exclaims that the Pop Trolls stealing the strings ‘is not what it said in our scrapbooks’, he replies that ‘Those are cut out, glued, and glittered by the winners’ – a metaphor for how White-centric narratives of progress frequently involve the exclusion of inconvenient facts and the voices of other, marginalised peoples. Prince D’s subsequent song, ‘It’s All Love’, comprises a rapped account of the Pop Trolls’ act of cultural appropriation and the way the other tribes felt compelled to flee to protect their music, with a sung chorus expressing sadness and betrayal on the one hand and hope for reconciliation on the other.

By the end, Poppy recognises the parallels between what the Pop Trolls did in the past and what Barb and the Rock Trolls are trying to do now, yet this does not fully shake her sense of mission. ‘I can make it right,’ she insists. ‘History’s just gonna keep repeating itself until we make everyone realize that we’re all the same.’ Again, King Quincy gently pushes back: ‘But we're not all the same…Denyin’ our differences is denyin’ the truth of who we are.’

Poppy takes time to fully absorb this lesson, but she espouses it herself in the film’s final scene, telling Barb: ‘A world where everyone looks the same and sounds the same? That’s not harmony…A good queen listens. Real harmony takes lots of voices.’ This spirit of diversity, egalitarianism, and togetherness is further captured by the song ‘Just Sing’, both in its lyrics (See me do it like nobody else/If we sing it all together/If we sing it all as one), and its musical arrangement, with different parts showcasing different voices and musical styles.

Ultimately, the film does not repudiate the qualities central to Poppy’s character as protagonist of Trolls and Trolls World Tour: when she tries to apologise to her father for ignoring his earlier warning, Peppy replies: ‘I’m so glad you didn't listen to me. You weren’t naïve about this world. You were brave enough to believe things can change. Braver than me.’ Yet there has been a subtle but substantial change in her aspiration: to achieve true unity through recognising difference, rather than just a shallow one by ignoring it. The film emphasises this as a basis for strong interpersonal relationships, as evident from Poppy’s reconciliation with Branch, whom she tells ‘I love that we’re different.’ Yet it also makes clear its wider application, as an almost pre-ideological value. As she tells the younger Trolls in an epilogue in which she simultaneously effectively addresses the young viewer too:

You have to be able to listen to other voices, even when they don’t agree with you. They make us stronger, more creative, more inspired. So whether your song is sad and heartfelt, loud and defiant, or warm and funky, or even if you’re a little bit of each, it’s all these sounds and all our differences that make the world a richer place. Because you can’t harmonize alone.

What I think is quite impressive about Trolls World Tour is its capacity to operate at these different levels, through using the story of the Troll Tribes as allegory for modern human history and music as an accessible but richly meaningful metaphor. It offers seemingly basic truisms about being yourself, and being nice and tolerant of others, even in the face of potential discord, which children can apply in their contained proto-social worlds. Yet it also ties them to more complex narrative strands and sets of ideas that serve the maturing child viewer as they begin to make connections between that world of interpersonal relations they know directly, and the more abstract society that exists beyond them.7

If you’ve enjoyed this post, you can show your appreciation by sharing it more widely, recommending the newsletter to a friend, and if you’d like, by buying me a coffee.

Along with the trilogy of feature-length Trolls films, there have also been two digitally animated television specials, Trolls Holiday (2017) and Trolls: Holiday in Harmony (2021), and two cartoon series, Trolls: The Beat Goes On! (2018–2019) and Trolls: TrollsTopia (2020–2022).

Sam Summers, DreamWorks Animation: Intertextuality and Aesthetics in Shrek and Beyond (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), ch. 3.

Ibid., pp. 84–86.

On the ‘Disco Sucks’ campaign, see: Gillian Frank, ‘Discophobia: Antigay Prejudice and the 1979 Backlash against Disco’, Journal of the History of Sexuality, Vol. 16, No. 2 (2013), pp. 276–306; Tim Lawrence, ‘Disco and the Queering of the Dance Floor’, Cultural Studies, Vol. 25, No. 2 (2011), pp. 230–243.

There is also I think significance in Hickory being revealed to be not one Country Troll but two Yodel Trolls in disguise, given the somewhat obscured influence of yodelling (and migration from Central Europe) on the musical traditions of the American South.

Again, it is perhaps far from a coincidence that the song she performs at Volcano Rock City, in celebrating her triumph, is ‘Barracuda’, which Heart’s Ann and Nancy Wilson wrote about their experiences of sexism and exploitation in the record industry.

Maturing child viewers and also, clearly, thirtysomething Dads.