Is It Worth the Aggravation?

Oasis’s reunification this week is the latest development in Britpop’s long afterlife, its leading lights continuing to carve out careers in the music industry well after the 1990s ended.

Please support my work by becoming a free or a paid subscriber to the newsletter. Paid subscribers can access my full archive of posts at any time, and are vital to me being able to continue producing and expanding this newsletter.

This post is part of the ‘Research and Reflections’ occasional series, consisting of pieces based on my ongoing academic research, as well as on my musings on and responses to current affairs and personal developments.

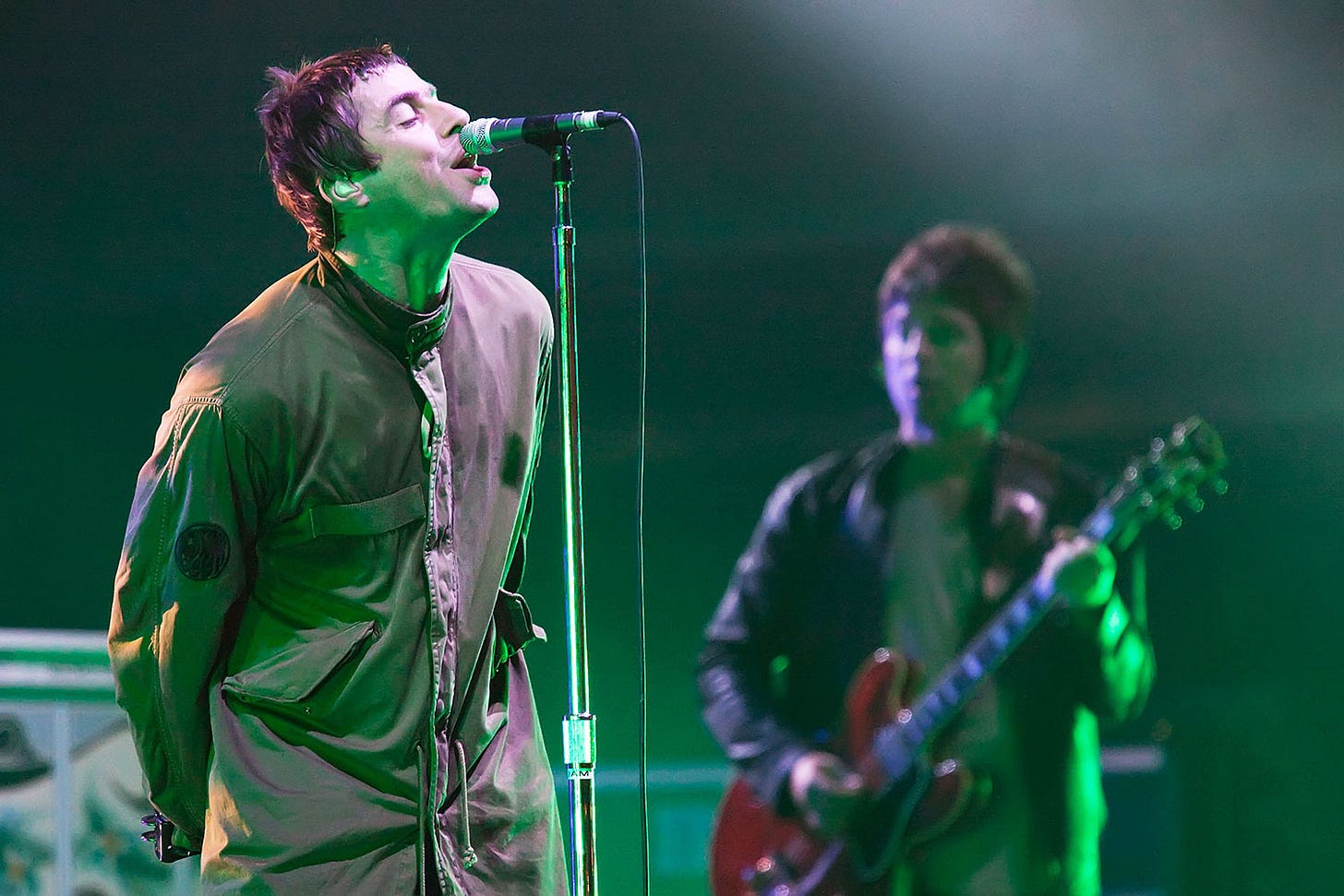

Today sees the publication – hurrah! – of my and Tobias Becker’s edited collection, The Uses of the Past in Contemporary Western Popular Culture: Nostalgia, Politics, Lifecycles, Mediations, and Materialities. Rather aptly, given that my own chapter in the book is on Britpop as heritage rock in the twenty-first century, Noel and Liam Gallagher announced this same week that they had decided to put aside their long feud and get (a version) of Oasis back together to tour the UK and Ireland next year. My suspicion is that they were waiting for me to finalise the proofs to steal the limelight away from us and render my chapter slightly out of date before it had even been published. It’s like ‘Country House’ versus ‘Roll With It’ all over again.

This is the latest and highest-profile of many groups labelled as ‘Britpop’ in the mid-1990s getting back together for one reason or another, while others were barely ever away, or else continued making music in new guises. I have written in the past for the newsletter about aspects of Britpop’s continued presence in public memory, and with it the culture and politics of the 1990s.

For this piece, and to mark the launch of the book and the less significant matter of the Gallagher brothers’ money-spinner, I want to turn my attention to that question of how Britpop musicians themselves have continued to work in the music industry over the three decades since initially coming to prominence.

From peak to trough

Britpop’s popularity reached its zenith in 1995. That year, Elastica, the Boo Radleys, Supergrass, Black Grape, the Charlatans, Blur, Oasis, and Pulp – each of whom were more or less convincingly bracketed under that label at one point or another – all enjoyed number one albums and top ten hit singles. It was that August when Blur and Oasis infamously competed for the number one slot in the UK singles chart. Blur won that battle, but Oasis emerged as Britain’s most popular band, with their (What’s The Story) Morning Glory? album the best-selling of the decade.

Yet even as major labels raced to sign up the newest British bands, Britpop’s heyday was passing. Blur’s eponymous fifth album, released in February 1997, and Pulp’s This Is Hardcore, released in March 1998, saw them pursuing new musical directions, while Oasis’s third album, Be Here Now, was launched in August 1997 to initial critical acclaim but subsequent sagging enthusiasm among record buyers and music writers alike. Britpop’s uneven international appeal made it harder to recoup the heavy investment in it, while majors frequently dropped bands whose follow-up albums failed to match the sales of their debuts.

There followed subsequently a drawn-out dissolution. Pulp released their final album, We Love Life in 2001, before going on hiatus in 2002. Suede did likewise in 2003. Long-running tensions within Blur led to the departure of their guitarist Graham Coxon while recording their album Think Tank in 2003; following its release, the rest of the band also decided to take a long break from making music together. Britpop-era bands Sleeper, Longpigs, Gene, Cast, Dodgy, Shed Seven, and Echobelly all also split during this period.

A long afterlife

However, some Britpop acts continued to record and perform long after others had split. Oasis remained hugely commercially successful, despite continuing to divide the critics, until breaking up in 2009. Supergrass persisted until 2010, and Ash, the Bluetones, and Ocean Colour Scene remain together to this day. Moreover, from the mid-2000s onwards, many Britpop-era bands who had gone their separate ways reunited: Kula Shaker in 2004; Marion in 2006; Dodgy, James, Shed Seven, and the Verve in 2007 (although the latter subsequently split up again); Blur in 2008; Cast and Suede in 2010; Pulp and Space in 2011; Lush in 2015; and now, of course, Oasis.

Many of Britpop’s leading figures also continued making music outside of the bands with whom they had first achieved fame. Blur lead singer Damon Albarn participated in diverse musical collaborations including co-creating cartoon band the Gorillaz with graphic artist Jamie Hewlett, travelling to Mali to work with local musicians, and forming super-group The Good, the Bad and the Queen, before releasing his own debut solo album in 2014. Liam Gallagher and other Oasis bandmembers, minus Noel, formed Beady Eye in 2009, releasing two albums before themselves splitting in 2014. Noel Gallagher formed his own solo vehicle, Noel Gallagher’s High Flying Birds, in 2011, with whom he has since recorded four albums.

Pulp lead singer Jarvis Cocker released solo albums in 2006 and 2009. Suede lead singer Brett Anderson briefly formed The Tears with former bandmate Bernard Butler, releasing one album in 2005, and thereafter released four solo albums prior to Suede reuniting. Butler, who originally left Suede in 1994, had in the interim released two albums with soul singer David McAlmont, either side of two solo albums. He subsequently formed the duo Trans with another guitarist, Jamie McKeown, releasing EPs in 2013 and 2014. More recently, he has released collaborative albums with musician Catherine Anne Davis in 2020, and with Irish actress and singer Jessie Buckley in 2022.

Between retrospection and reinvention

Britpop’s transition from zeitgeist to heritage rock was inherent its own origin myths and developed through its progress past infancy. This heritagisation became a more conscious process from the late 1990s, as Britpop came to be seen as something that had happened and passed, supplanted by new developments in alternative rock and popular music more generally, and therefore ripe to be revisited. The bands themselves were at the heart of this trend, although it would be wrong to characterise their post-1990s activities together as entirely backward-looking, given the commitment of many of them to making and releasing new music. Suede, Kula Shaker, and Space, for example have released four albums each since their reunifications. By contrast, Shed Seven have released only two new studio albums since reuniting 16 years ago: 2017’s Instant Pleasures, and 2024’s A Matter of Time. Yet they have also played over 250 concerts in that time, demonstrating – in quantifiable terms – a preference for gigging over recording.

Revisiting the past is an intrinsic part of performing live, particularly for acts with sizeable back catalogues behind them. In these cases, there is a tension not only between creative and commercial imperatives, but also between different commercial ones: on the one hand, promoting their latest material; on the other, meeting fans’ expectations and playing old established favourites. On their 2008–09 tour promoting their seventh album, Dig Out Your Soul, over half of the songs on Oasis’s set lists were originally recorded by the band in 1994 and 1995, compared to just over a quarter from the new album.

Furthermore, after forming his High Flying Birds project, Noel Gallagher continued to perform a significant quantity of Oasis material live. By contrast, Pulp songs have only composed a small portion of Jarvis Cocker’s live solo performances; likewise Blur songs for Damon Albarn. In such cases, the commercial imperative to use and monetise well-known back catalogues appears to have been at least partly trumped by a creative impulse to explore new directions and assert one’s own identity as an artist distinct from previous endeavours, perhaps assisted by the financial security such endeavours nonetheless provided.

Reflecting on past glories

Britpop artists have often displayed discomfiture with the question of its cultural significance, and by extension their contribution to it, responding to questions about it with hesitancy and self-depreciation. Accompanying this distancing strategy has been an acknowledgment that at least some of their experience of the period were arduous, often in ways that fragmented the dominant positive, unifying narrative of what Britpop had been. For example, Elastica lead singer Justine Frischmann, who had also been the long-term partner of Damon Albarn at the time, admitted to BBC Radio’s Steve Lamacq that she wished she had left the band after its first album, before the pressure had begun to build upon them. For others, the relatively young age at which they sampled success soured an experience they were not quite ready for.

Being interviewed in 2014, Blur bassist Alex James, generally far more comfortable talking about Britpop than many of his former peers, speculated as to the reasons for that more general reticence:

People never want to talk about the past, really, they want to talk about the future, really, no one seems to like to be seen as living on past glories, y’know, and it was twenty years ago.

This seems an accurate insight. Musicians associated with Britpop in the 1990s have continued to pursue creative fulfilment and autonomy, and commercial and critical success, in a sector that has historically venerated youth and viewed artists as having a ‘shelf-life’. Their platform for doing so, however, came from past achievements and associations that could reinforce those same ageist paradigms, and whose relative popularity threatens to relegate those artists and their careers to posterity.

Having often decried the workings of the music industry that they had experienced disappointment and disillusionment with during the 1990s, former Britpop artists have often expressed a sense of liberation from their former paymasters, and from old routines that need no longer be obeyed. Bernard Butler, for example, stressed his disinclination to ever return to a long-term band set-up, or to the cycle of releasing albums and touring them, preferring to keep a low profile and release EPs. Meanwhile, Justine Frischmann, who moved to Colorado to pursue a career in visual art, and gave up making music entirely, emphasised the freedom she felt in no longer having to work with other people in making her art, and in the anonymity that she could now enjoy in her private life.

At the same time, Britpop artists have negotiated their relationships with their pasts in ways consistent with their contemporary professional identities and aspirations. This is evident, for example, in the way they have explained their decisions to reform their former bands. Nigel Clark insisted that Dodgy’s reunion in 2007 had been ‘for creative reasons, not for the nostalgia’. Rick Witter of Shed Seven, by contrast, repeatedly emphasised his band’s aversion to returning to the strains of writing new songs and dealing with record companies, remaining content instead to entertain their existing fan base by playing their former hits.

While being interviewed by Steve Lamacq back in 2014, Noel Gallagher made the case for balancing retrospection with progress. He explained that he enjoyed revisiting old songs he had written when playing in concert, providing that he was writing new material as well. He also insisted an Oasis reunion did not interest him creatively, but that he would do it for ‘a stupid amount of money’. With it now rumoured that he and Liam could make as much as £50 million between them from next year’s shows alone, it would appear the Gallagher brothers have deemed there is in fact something worth working for.

If you’ve enjoyed this post, you can also show your appreciation by sharing it more widely, recommending the newsletter to a friend, and if you’d like, by buying me a coffee.